Deep River,

Deep River, Lawd,

Deep River, Lawd,

I want to cross over in a ca’m time.

—From American Ballads and Folk Songs, by John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax

Series Editor: David Evans, Ph.D.

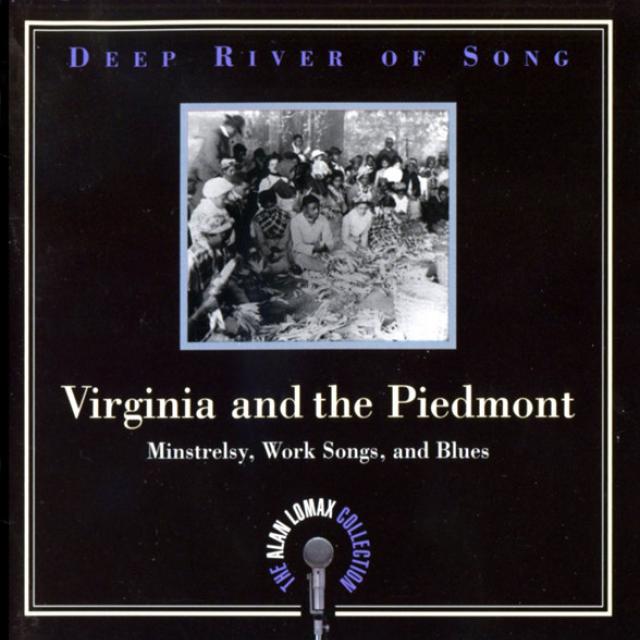

More than half a century separates us from the performances in this series, and nearly all of the artists who gave them to us have “crossed over” in that time, leaving us these treasures in trust so that we might be delighted, informed, and edified by them. Each song tells its own story, but together they form an epic of a people seeking to ford a turbulent river of oppression and disadvantage, who gave us another life-giving river of untold depth and riches: a deep river of song from which all may draw.

It was this that John Lomax and his son Alan sought to preserve and document when they began their field recording for the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress in 1933. It was this same river that Alan Lomax sought to replenish when he and Peter B. Lowry reviewed more than a thousand field recordings of black music made by the Lomaxes in the South, the Southwest, Haiti, and the Bahamas.

Alan Lomax spent the summer of 1978 in Mississippi with John Bishop and Worth Long, shooting the program Land Where the Blues Began. “I discovered to my consternation that the rich traditions which my father and I had documented had virtually disappeared,” he wrote. “Most young people, caught up by TV and the hit parade, simply did not know anything about the black folklore that their forebears had produced and which had sustained and entertained generations of Americans. I resolved to try and do something about this situation, so far as I could.”

Lomax and Lowry eventually compiled 12 albums at the Library of Congress, with more planned; these were “organized in a way that might help to show blacks and other Americans the beauty, variety, the regional traits and African characteristics of this great body of song.” These albums bear witness to a transformative moment when a new singing language, new musical forms, and thousands of songs that belong in the first rank of human melodies were created. They evoke now vanished musical worlds, showing how black style developed as settlement moved westward from the Carolinas to Texas and how regional styles branched forth along the way.

“[This music is] a thing of very great beauty—a monument to the extraordinary creativity of the black people of North America,” Lomax wrote. “No song style exists anywhere that can surpass this material for sheer variety, originality, and charm. Yet its most genuine aspects are little known today and are fast fading out of currency under the pound of the media.” He hoped that this series could help “restore to the American consciousness, and especially African-Americans, a heritage that is about to be altogether lost.” Perhaps now, as we have crossed over into the twenty-first century, we are close enough to the “ca’m time” of songs and dreams for this restoration to take place.