Selections:

Introduction by Alan Lomax to Joe Cloud; “Devil’s Dream” (Joe Cloud); “Squaw Dance” (Joe Cloud); “Devil’s Dream” (Patrick Bonner) **Note, Bonner’s recording of “Devil’s Dream” has been edited to remove skips and get closer to the form of the original performance.

Recorded: October 16, 1938, Odanah, Wisconsin; August 24, 1938, Beaver Island, Michigan

Performers: Joe Cloud, fiddler; Patrick Bonner, fiddler

Activity 1: What Do You Know about American Indian Music?

- Teacher guides a brainstorming session of students’ ideas about American Indian music: instruments, sounds, places they may have heard it.

- Students engage in an instrument scavenger hunt with the following photo. Q—What instruments do you see in this family portrait of Mrs. Thomas, her two children, two sisters, and brother? **Note, This is likely an Ojibwe family connected with the L’Anse Indian Reservation in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. (fiddles, guitars, mandolin, autoharp)

- Teacher revisits discussion about American Indian music to see if the photo changed students’ ideas.

Activity 2: Meet Fiddler Joe Cloud of Odanah, Wisconsin

- Students read or listen to this introduction to fiddler Joe Cloud, the only performer Alan Lomax recorded in Wisconsin and his only recording of American Indians from the Great Lakes region. **Note, Lomax had leads to many other American Indian American fiddlers, but he only recorded Joe Cloud.

"These fiddle tunes are being recorded by Joe Cloud in Odanah, Wisconsin, on October 16, 1938, for the Archive of American Folk-Song in the Library of Congress. Mr. Cloud is 53 and has the blood of the Chippewa [also known as Ojibwe] flowing in his veins. He has played the fiddle since he was 15 years old and learned to play from his father, who was also a fiddler. He plays entirely by ear." -

Teacher adds the following information:

- Joe Cloud played fiddle in a trio with his son (banjo) and daughter-in-law (piano) for local weddings and community dances.

Q — Who is Joe Cloud?

Q — How did he learn to play fiddle?

Q — Where did he play the fiddle? - Students locate Odanah, Wisconsin and the Bad River Ojibwe reservation on a map.

- Teacher introduces students to the history of fiddling among the Ojibwe.

- The fiddle and its tunes were introduced to the Ojibwe peoples of the Great Lakes region by Scots and French-Canadian fur traders as early as the 1600s.

- Intermarriage between European trappers/lumberjacks and American Indian women helped make European music and dance more accepted among American Indian peoples.

- After laws were passed banning American Indian religion— with its drums, rattles, flutes, and songs—fiddle music became even more important.

- American Indian fiddling often took place at lumber camps, taverns, dance halls.

- American Indian fiddlers played both their own versions of European dance tunes and American Indian tunes (pre-dating contact with Europeans). You are about to hear examples of each played by Joe Cloud.

- This tradition is alive and well today!

Activity 3 : The European Tradition: “Devil’s Dream” 1

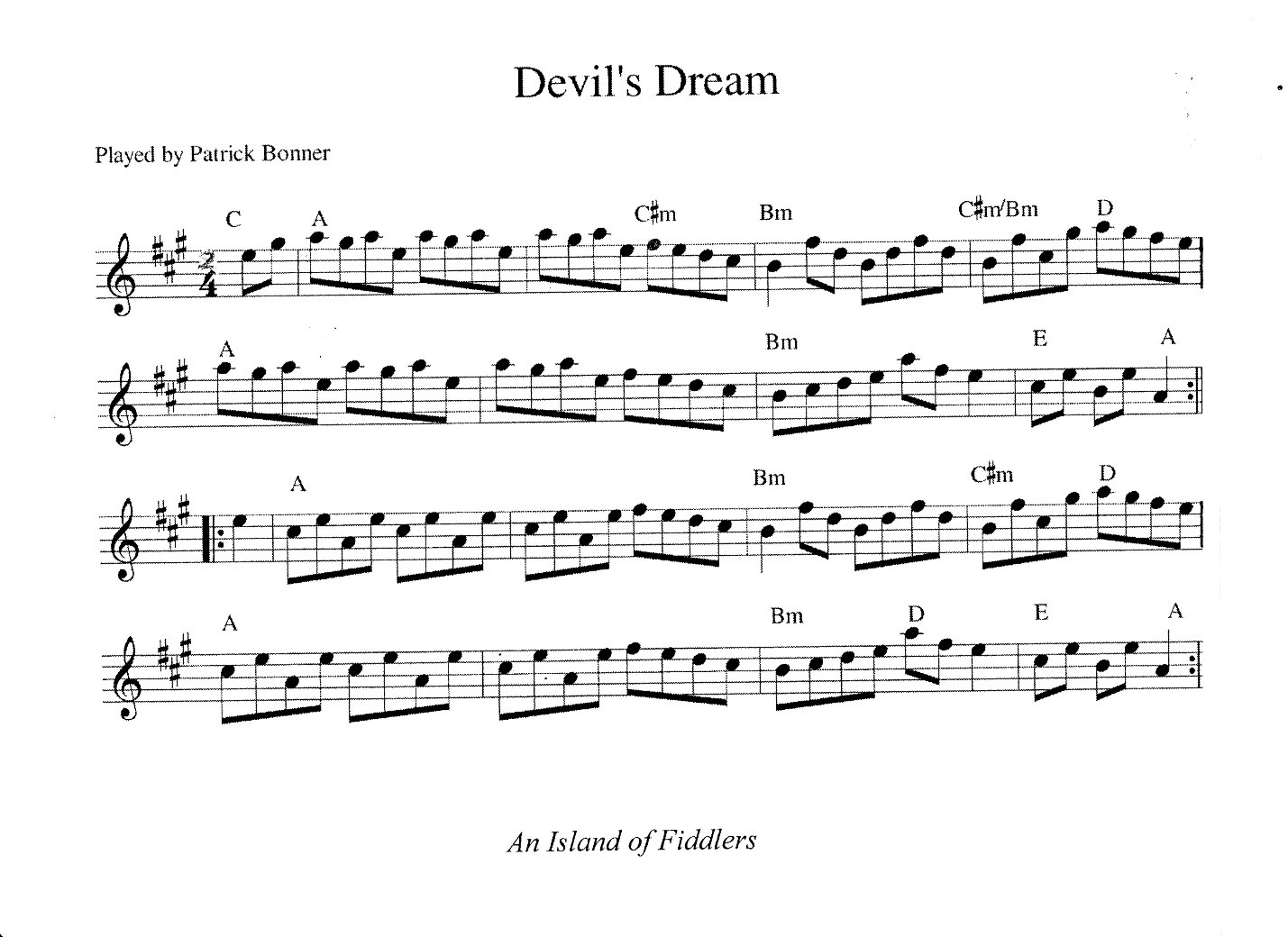

- Students play or listen to the teacher play the basic melody of “Devil’s Dream” in the transcription below. Alternatively, students listen to a recording of “Devil’s Dream” by Beaver Island (Michigan) fiddler, Patrick Bonner, whose version is slower and easier to follow than the Joe Cloud version.

-

Students identify the main A/B form sections by doing a different activity for each, holding up “A” and “B” cards, etc.

Q — What is the form of the piece? (AABB AABB)

Transcription from An Island of Fiddlers by Glenn Hendrix. Used with permission. - Students listen to the reel “Devil’s Dream” played Joe Cloud as an example of standard white/European-style fiddle tune played by an Ojibwe fiddler. Students clap along with the beat.

- Teacher introduces/reinforces the concept of meter, in this case 2/4, which underlies their clapping.

- Students maintain the beat by clapping or marching, and while simultaneously marking the main A/B form sections by doing a different activity for each, holding up “A” and “B” cards, etc.

- More advanced students divide into two groups (A and B, as in the form of the piece), and count the number of beats in their section.

Q — How many beats in each section? [A (16) and B (16)]

Q — How many total beats in the standard AABB AABB fiddle tune? [32 beat form]

Activity 4 : The American Indian Tradition: Squaw Dance

- Teacher prepares students to listen to “Squaw Dance,” which Joe Cloud played for Alan Lomax right after he finished recording “Devil’s Dream.” Teacher leads discussion on the title “Squaw Dance,” which here means a “women’s dance” without the negative connotations associated with the term “squaw.”

- Joe Cloud plays a traditional Ojibwe women’s dance on fiddle.

- This tune is still recognized by present-day Ojibwe powwow drum groups as a women’s dance, in which women move slowly in a counterclockwise circle with their feet maintaining contact with “Mother Earth.”2

- More traditionally, this piece would have been sung to drum accompaniment.

- Students listen to “Squaw Dance” as an example of a traditional Ojibwe tune (in contrast with the European-style fiddle tune “Devil’s Dream”)

Q — Do you hear harmony or just one melodic line? (single melody line, a characteristic of American Indian American music, usually a solo or unison singing.) **Note, fiddlers for European-style community dances often played alone, too, if there was no accompanying instrument available, but often harmony parts were played by piano, another fiddle, guitar, etc. In the Thomas family photo, some instruments likely played melody and others accompanied with harmony parts. Teacher could illustrate harmony by playing “Devil’s Dream” with the suggested chords from transcription.

Q — Can you clap along? (There is no right or wrong here, but it won’t be as obvious as in “Devil’s Dream.” This is not a song in 2/4 time! Pieces like this would have been accompanied by drum. Without a drum, we can’t really know the underlying pulse as Joe Cloud felt it, but there is an underlying pulse.) - Teacher explains that the shape of traditional American Indian American melodies often goes from high to low (descending melodic contour).

- Students act out the descending melodic contour with body movements.

Q—Can you sing the highest note? The lowest note? - Teacher points out that traditional American Indian American tunes like “Squaw Dance” typically have one main section, BUT it can be tricky! Many melodies (like this one) repeat the last part of the tune—a partial repetition (**Formerly called incomplete repetition, but scholars now prefer other terms.)

- Students listen again and raise their hand or do an activity when they hear the partial repetition. **Hint: Listen for the lowest note the first time. The partial repetition starts right afterwards (at 12.5 seconds from the beginning). Listen for the lowest note the second time, and the melody is completed. It then repeats.

Q—How many repetitions of the one main section do you hear? (3, with a partial repetition at the end.) - Teacher points out features of “Squaw Dance” that are characteristic of traditional Ojibwe songs (as appropriate to student levels):

- Repetition

- Monophonic texture (solo or unison melody line)

- Underlying pulse (usually played on drum—Joe Cloud played it for Lomax out of the typical setting for performance—hence no drum and the pulse is hard to determine)

- Descending melodic contour

- Traditionally used to accompany ceremonial dance (as opposed to social square dancing, etc.)

- This tradition continues today.

1. Thanks to Anne Lederman whose writings and insights shaped this lesson. See especially “Old Indian and Metis Fiddling in Manitoba: Origins, Structure, and Questions of Syncretism,” (Canadian Journal for Traditional Music (1991): 2-13. ↩

2. James P. Leary, Folksongs of Another America, Field Recordings from the Upper Midwest, 1937-1946 (University of Wisconsin Press, Dust to Digital, 2014), p. 104. ↩

Extensions:

Explore music of American Indians in your community, region, or state.

View the documentary film Medicine Fiddle about American Indian/Métis fiddlers in the Great Lakes, Great Plains, and Canadian Prairie provinces. Film by Michael Loukinen, Copyright: 1991, Michael Loukinen, 01 hours, 21 minutes, Color, Original format: Film: 16mm, 1991. Distributor: Northern Michigan University, Up North Films.

Credits:

Background information on Joe Cloud comes from James P. Leary, Folksongs of Another America, Field Recordings from the Upper Midwest, 1937-1946 (University of Wisconsin Press, Dust to Digital, 2015). p. 104.

Thanks to Glenn Hendrix for the transcription of “Devil’s Dream” as played by Patrick Bonner, from An Island of Fiddlers, Fiddle Tunes of Patrick Bonner (Beaver Island, Michigan, Self-Published by Glenn Hendrix, 2008.)

Thanks to Anne Lederman, ethnomusicologist and fiddler, for providing suggestions for this lesson plan.

Lesson Plan by Laurie Kay Sommers

With generous support from the NEA