Selection: Hammer Ring

Performers: Unidentified man

Recorded: Clemens State Farm, Brazoria, Texas, April 1939

Activity 1: (Grades 4-6, 7-9, 10-12, C/U)

- Play the recording multiple times, focusing student attention with a new question prior to each repeated listening. Note that the listening may be as short as 01’-10” (one “round”, stanza, or verse), or 01”-20” (two “rounds, stanzas, or verses), or of a greater length to listen to further verses and their variations, as preferred.

- Who is singing? [Male soloist and male group]

- What are the words for the group response to the solo male voice’s call? [“Hammer Ring”]

- Can you count the number of times that the response, “Hammer Ring”, is sung?

- Within the first “round” (or stanza, or verse)? [4 times]

- Within the first 20 seconds (the length of two “rounds”)? [8 times]

- Does “Hammer Ring” sound the same way every time? [No. Even in the first “round”, or stanza, or verse, “Hammer Ring” alternates between a pitch-rising phrase and a stay-the-same-pitch phrase.]

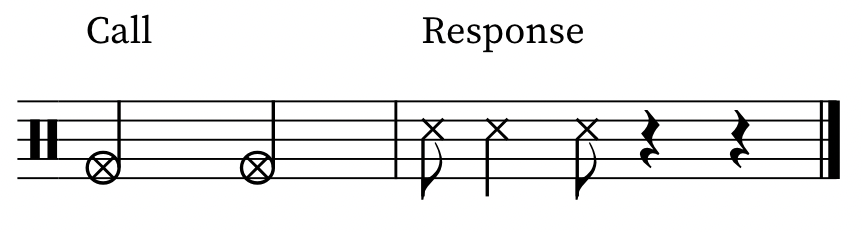

- Practice stepping the “call” and clapping the “response” rhythms while listening to the recording. Note that this two-measure pattern is repeated twice for each “round”, stanza, or verse, and continues as a steady two-measure movement of eight beats all through the recording. This step and clap underscores the solo-group “call-and-response” construction of the song.

- Sing the response to the call, “Hammer Ring”, alternating between the first pitch-rising phrase and the second stay-the-same-pitch phrase

- Listen again to the recording, and pick out the lyrics of the soloist’s “call”, while singing the alternating response phrases on “Hammer Ring”.

Round/Stanza/Verse 1 -------------- Response (preliminary) Call: Gonna buy me a hammer Response Call: Well the captain got the hammer Response Call: Well the captain got the hammer Response Round/Stanza/Verse 2 Call: It’s a ten-pound hammer Response Call: Well, ten-pound hammer Response Call: Well, went in the wild wood Response Call: Well, went in the wild wood Response Round/Stanza/Verse 3 Call: Well, jumped on the ladder Response Call: Well, jumped on the ladder Response Call: With a ring in my hammer Response Call: With a ring in my hammer Response Round/Stanza/Verse 4 Call: Whoa, my hammer Response Call: Well, my hammer Response Call: With the ringing and the ladder Response Call: With the ringing and the ladder Response Additional Rounds/Stanzas/Verses - Sing the song softly with the recording, attempting to match the slow tempo and the particular enunciations of the words.

- Add the stamp-clap pattern while singing (and swinging) the song at a slow tempo with the recording, and then without the recording.

- This song has been sung in many versions, with lyrics for the “call” that are improvised and sometimes referring to Biblical stories like that of Noah and the Ark. As the song’s melody is known, try out these lyrics from another version of the song for the “call”, and consider improvising new lyrics. Regardless of the lyrics, “Hammer Ring” can be continued as the response.

Broke the hand on my hammer.

Got to hammerin’ in the Bible.

Gotta talk about Noah.

Well, God told Noah.

You is a-goin’ in the timber.

You argue some Bible.

Well Noah got worried.What you want with the timber?

Won’t you build me a ark, sir?

Well, Noah God, sir.

How high do you want it?Build it forty-two cubits.

Every cubit have a window.

Well it started in to rainin’;

Old Noah got worried.He called his children.

Well, Noah told God, sir.

This is a very fine hammer.

Go the same old hammer.

Got to hammerin’ in the timber.

Activity 2: (Grades 4-6, 7-9, 10-12, C/U)

- In Texas and throughout the American South, many of the prisons and work farms were based on agricultural models found in West Africa. The songs that were sung by free men in Africa, who worked for their families and communities, planting and harvesting crops, were typically poetic expressions of life, relationships, and hopes and dreams. For enslaved African Americans, work songs were sung for survival, to sustain the work, to keep the workers together, so that no one worker would trip, or fumble, or could be singled out and punished for working too slowly or in an unsteady fashion. Today, there are 64 state-operated prisons in Texas alone, and many more spread throughout the U.S., where many African Americans are “doing time”, that is, serving a prison sentence. At 33%, a disproportionate number of the incarcerated population in Texas is African American. While work gangs are no longer standard practice, when John and Alan Lomax travelled Texas and throughout the south to the segregated prisons in the 1930s, they collected and recorded a treasury of work songs that African American inmates vowed were the means by which they got through the days of harsh physical labor. Explore the old work songs sung by prisoners, such as “Early in the Mornin’”, “Take This Hammer”, and “Stewball”.

- The meaning of “Hammer Ring” might at first appear to be the work of a jeweler who is shaping a ring of silver or gold, rounding it out, and engraving it with intricate designs. Another meaning might reach to the sonic, as the sound of a metal hammer that makes contact with a steel spike, stud, or nail produces a ringing sound. However, renditions of “Hammer Ring” do not refer to fine jewelry, nor to the sonic properties of a high-pitched ring. Instead, this African American work song has functioned as a cross-cutting, timber-cutting song, one that is sung to the swing of an axe to the base of a tree trunk. This work song has been recorded in many versions and variations, with most of them originating from prison laborers on the plantations and in the penitentiaries of Texas and elsewhere in the South. Like so many work songs, the slower tempo is meant to match the laborer’s movement, and most certainly the swing of a heavy axe could take time from the wind-up to the contact with the timber’s surface. Emulate the movement of chopping a tree with a 10-lb or 20-lb axe, and experiment with different tempos by which this movement can be reasonably accomplished.

- Historically, the singing voice was the principal instrument for enslaved African Americans. Whether they worked in the fields or cared for their young children in the home and yard, the voice was the way of communicating songs of solidarity or soothing lullabies. Alone or together, in unison or in the call-and-response mix of soloist and group, the songs of African Americans were frequently embellished, improvised, and otherwise altered in expressive ways of rich tones and textures. The human voice is capable of many timbres and techniques, and African Americans have fashioned a wide spectrum of vocal genres that are well worth exploring—from Marian Anderson, James Brown, Aretha Franklin, Prince, Paul Robeson.

- For enslaved African Americans, the hands and feet were important for creating rhythmic beats. In church, in dance halls, or on the back porch, there was plenty of hand-clapping and foot-stamping for feeling the pulse and creating rhythmic beats. Clearly, such body percussion was not possible if the songs were sung during labor, when hands were occupied and feet functioned to steady and stabilize workers when they were using tools. But if that song was sung as recreation on a Saturday night, the hands and feet were sure to be in motion to accompany singing and instrumental tunes. Discover and invent a variety of rhythms for the engagement of hands and feet while singing.

Lesson plan by Patricia Shehan Campbell