Selections:

Got On My Travelin’ Shoes

Recorded: Central Park, New York City, NY (August 1965)

Performers: Reverend Gary Davis and the Georgia Sea Island Singers (John Davis, Peter Davis, Mable Hillery, Bessie Jones, Emma Ramsay)

"Jonah"

Recorded: Moving Star Hall, Johns Island, SC (August 1983)

Performers: Janie Hunter and the Moving Star Hall Singers

"Eli, Eli (Somebody Call Eli)"

Recorded: Moving Star Hall, Johns Island, SC (August 1983)

Performers: Bertha Smith and the Moving Star Hall Singers

Activity 1: Musical

- Attentive (listening)

- Before starting the recording at the beginning, ask the students to listen for instrumentation and form (or, direct half of the students to listen for instrumentation while the other half listens for form).

- Play about a minute (go no further than 1:20) of the recording, then ask the students the following questions:

- What sounds did you hear? (Answer: voices, tambourine, hand claps)

- What is the form of the piece? (Answer: call-and-response)

- Replay a short section of the recording to redirect students’ attention to these elements.

- Engaged (listening)

- Play about 30 seconds of the recording from the beginning. Direct half the students to trace the melodic contour of the call and the other half to trace the melodic contour of the response. Model (both) to encourage participation.

- Facilitate a class discussion over the following three questions:

- Do the calls change? (Answer: Yes)

- Do the responses change? (Answer: Yes)

- How do they change? (Answer: The calls change almost every time – Rev. Davis varies the lyrics of the call or the melodic contour of the call as he leads the group through the spiritual. The changes are not dramatic; the general shape of the calls remain constant. The responses alternate between two versions: the first response ends with the voices moving melodically up on “shoes”, then the second response ends with the voices moving melodically down on “shoes.”)

- Enactive (listening, performing)

- Play at least 30 seconds of the recording (go no further than 1:20) from the beginning. Direct the students to sing the response part (“got on my travelin’ shoes”) with the recording.

- Sing along to model; draw attention to the harmonization in the response and encourage students to sing along in harmony.

- Repeat this action until students can confidently sing the response part, leading them into performance of this song without the recording.

- Creative (performing, improvising) **

- Perform “Got On My Travelin’ Shoes” with the students in the style of Rev. Davis and the Georgia Sea Island Singers. Once the class can confidently sing the response without the recording, designate a caller. The caller can use a constant call – “travelin’ shoes, lord” or “travelin’ shoes, now” etc. but encourage student callers to vary their calls in the style of Reverend Gary Davis.

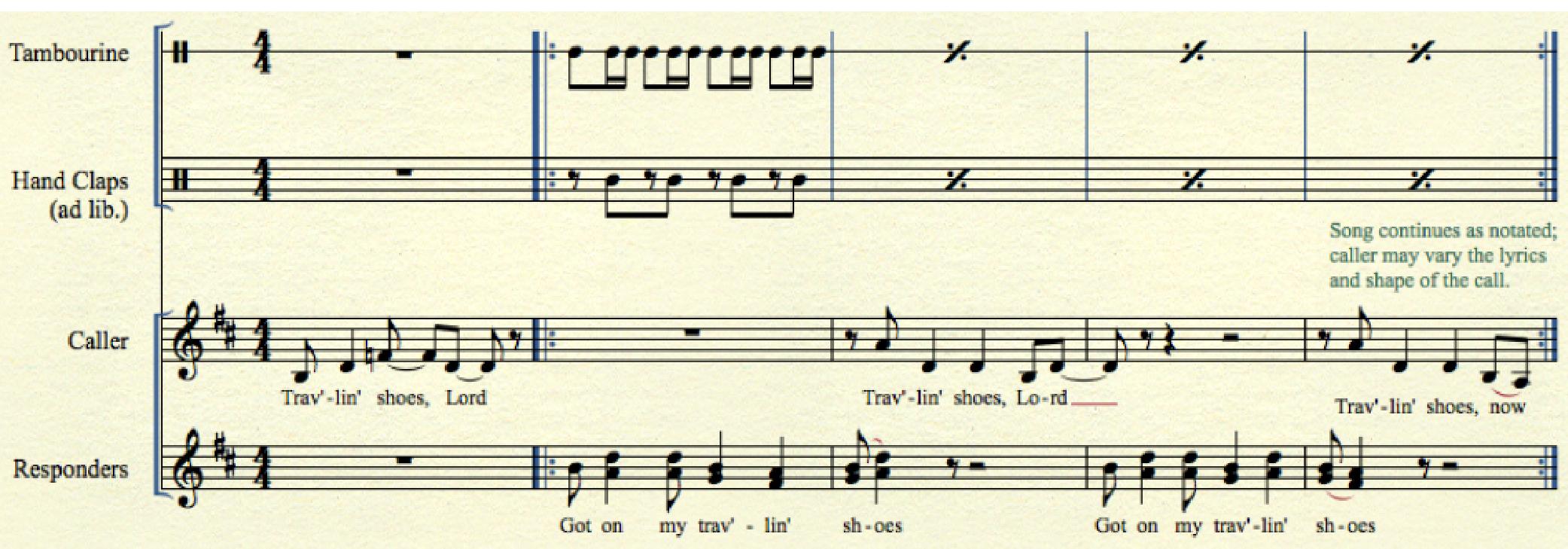

- Add a tambourine and have responders clap along to enrich the texture.

- Rotate assignments so multiple students have an opportunity to call.

**NOTE: This song is best performed after students learn the cultural, historical, and stylistic context of the song. See Activity 2 below.

Transcription of the opening of “Got On My Travelin’ Shoes” as performed by Reverend Gary Davis and the Georgia Sea Island Singers in Central Park, 1956

Activity 2: Contextual

- The Spiritual

- Lead students through a discussion of the spiritual as a genre of music:

- The African-American spiritual tradition originated in the southern United States. With roots both in European-American Christian hymns and African rhythms and aesthetics, spirituals were (and still are) an integral part of African-American musical life.

- African-American spirituals are not usually written down or notated like music in the European-American classical tradition. Enslaved African-Americans were almost always forbidden to learn how to read or write because slave owners knew that educated people would be harder to control. African-Americans passed down songs, dances, stories, recipes, and other customs as part of a vibrant oral tradition which continues to this day.

- Because spirituals like “Got On My Travelin’ Shoes” were not originally written down, the instrumentation, lyrics, rhythms, and melodic contour can vary greatly from one performance to the next. For this reason, musicians well-versed in the spiritual tradition are skilled improvisers.

- As a social activity, spirituals emphasize participation, allowing many different modes of expression including movement (dancing, stepping, swaying, clapping, stomping, waving, etc.) and vocals (singing, shouting, chanting, etc.).

- African-American spirituals traditionally have close ties to religion and are used in worship, but some spirituals have had other uses. Throughout history,spirituals have been used by AfricanAmericans and their allies to resist systemic oppression as codes, rallying cries, and protest. Spirituals have also influenced many other genres of music, including blues, gospel, and soul music.

Exercise 1: Movement and Performance in "Jonah"

- After students have learned the background history of the African American spiritual, have them watch the short video excerpt of “Jonah” as performed by Janie Hunter and the Moving Star Hall Singers, directing their attention to the movement and participation style of the performers, here.

- Ask students the following questions:

- What do you see/hear the performers doing while they sing “Jonah” in this excerpt? (Answer: feet tapping, clapping, swaying/rocking, fanning)

- Watch the excerpt a second time. What rhythms do you hear in the foot-tapping and the clapping? (Answer: in the beginning of the recording, the performers are tapping their feet on each strong beat: 1, 2, 3, 4. When they begin clapping, they clap on beats 2 and 4. This is a common pattern in African-American spiritual music called backbeat.)

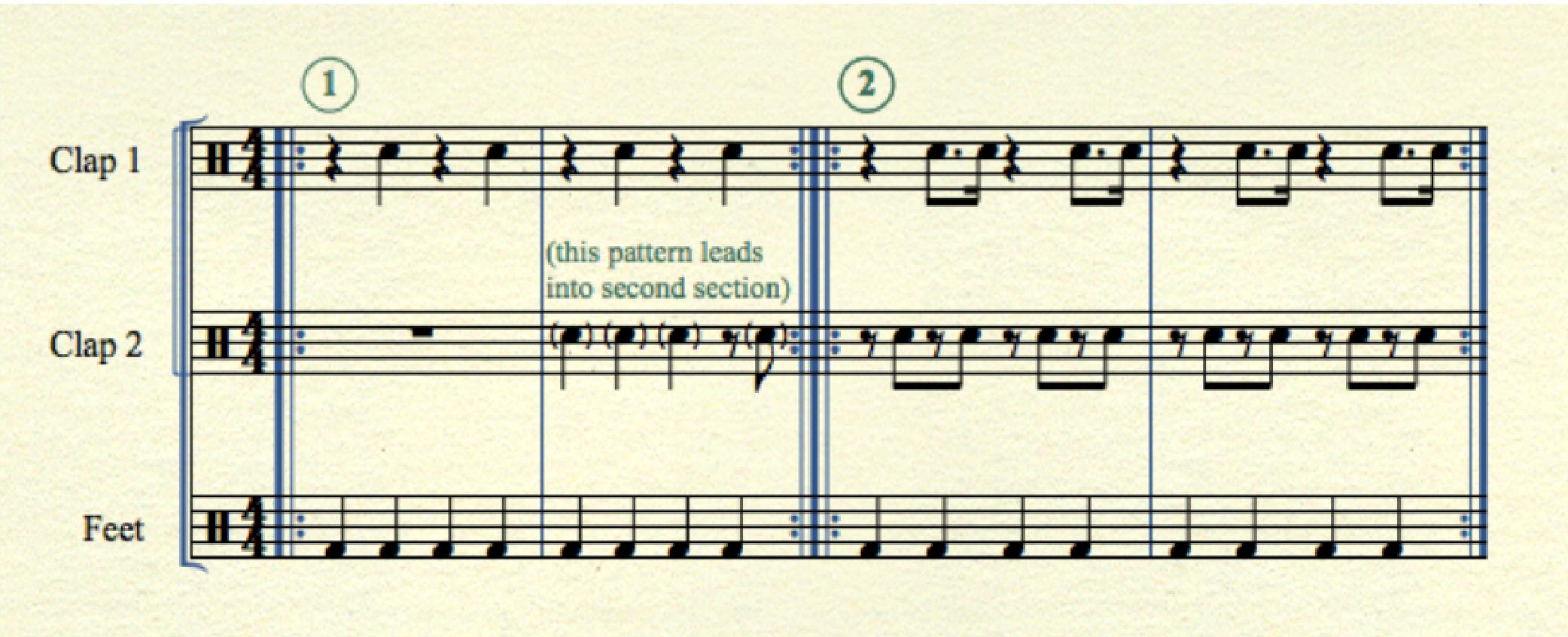

- How do they change? (Answer: The clapping changes towards the end of the recording with two distinct rhythms that interlock, creating a polyrhythmic texture.)

- What signals the change? (Answer: The woman in the back row leads the shift to the second clapping pattern by introducing a new rhythmic pattern.)

- After the discussion on clapping and movement in “Jonah,” lead students through a rendition of the performance. Sing and clap along with the recording. Notation for the clapping patterns is provided below:

Transcription of the clapping parts to “Jonah” as performed by the Moving Star Hall Singers, 1983

- Lead students through a discussion of the spiritual as a genre of music:

- Call-and-response

- Call-and-response is a musical form that is common in African-American spirituals, such as “Got On My Travelin’ Shoes.”

- Call-and-response can be thought of as a musical conversation between multiple participants. The caller or leader acts as a guide for the musicians, starting the song and facilitating its development. The caller sets the tone throughout the performance, pushing and pulling on the energy of the participants. The responders follow the leader with set lyrics. This form allows for maximum participation, emphasizing inclusivity and community.

- When used in worship in the African-American spiritual tradition, the caller is usually a preacher or other community leader while the congregation acts as the responders.

Exercise 2: Call-and-response in “Eli, Eli”

- Have students watch the short video of “Eli, Eli” as performed by Bertha Smith and the Moving Star Hall Singers. Instruct the students to raise their hand when the call is being sounded (on “Eli, Eli) and to place their hand on their chest when the response is sounded (on “somebody call Eli”). Repeat this activity as necessary. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5jZwleyOcpU

- Ask the students the following questions:

- Is the call always the same? What about the response? (Answer: Like the earlier examples – “Got On My Travelin’ Shoes” and “Jonah” – both the calls and the responses vary slightly during the performance of the piece as it progresses.)

- What do you notice about the clapping and the movement for “Eli, Eli”? (Answer: Like in “Jonah,” the clapping patterns begin with a backbeat and move into a polyrhythmic texture. The performers are also tapping their feet on the beat, and swaying as they sing.)

- Next, have students sing “Eli, Eli” with students taking turns being the caller (“Eli, Eli”) and the responders (“somebody call Eli”). Incorporate the clapping patterns notated in Exercise 1 (“Jonah”).

Activity 2 Extension: Further information about the performers of “Got On My Travelin’ Shoes”:

- Reverend Gary Davis

- Reverend Gary Davis was an African-American guitarist, composer, and ordained Southern Baptist minister. Born in South Carolina in 1896, Davis was completely blind by the age of ten. He achieved fame through his renowned skills as a gospel blues-style guitarist and was a noted influence on many popular American musicians, including Bob Dylan. Students of Davis include folk musician Dave Van Ronk and Bob Weir of The Grateful Dead.

- Davis toured the United States and Great Britain in the mid 1900s. His music (much of it original) was a lively combination of African-American spirituals, square dance music, and American marches.

- In 1956, Davis performed at the Central Park Music Festival in New York City, where his performance of “Got On My Travelin’ Shoes” with the Georgia Sea Island Singers was recorded by Alan Lomax.

- Further information can be found here.

- The Georgia Sea Island Singers

- The Georgia Sea Island Singers are an African-American folk music group from Sea Island, Georgia. The Singers maintain a strong connection to the Gullah culture of coastal Georgia and the Carolinas.

- Native to the coastal islands of Georgia, Florida, and the Carolinas, the Gullah people are African-Americans with close ties to their West African roots. During the Civil War, the enslaved people of the Sea Islands area were freed from their bondage relatively early compared to other Southern blacks and were largely left alone in the sixty years following the war. The Sea Islands also became a refuge for former slaves from the nearby Bahamas. As a result, the Gullah people cultivated a rich and unique tradition. Their music features aspects of West African traditions, including call and response form.

- Of the Georgia Sea Island Singers, Bessie Jones is the most famous. Born on mainland Georgia, Jones moved to the Sea Islands as a young girl. She helped found the Georgia Sea Island Singers in the mid-1900s, a folk group that featured traditional songs and musical games of the Gullah people. Many of their performances were recorded by Alan Lomax.

- In 1956, Jones and the Georgia Sea Island Singers performed at the Central Park Music Festival alongside Reverend Gary Davis.

- Further information can be found here.

- The Georgia Sea Island Singers are an African-American folk music group from Sea Island, Georgia. The Singers maintain a strong connection to the Gullah culture of coastal Georgia and the Carolinas.

Lesson plan designed by J. Mike Kohfeld, transcriptions by J. Mike Kohfeld