by Ellen Harold and Peter Stone

Guy Carawan (b. Los Angeles, 1927) is best known for introducing the song that became the anthem of the Civil Rights movement, “We Shall Overcome,” to the founding convention of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNNC) in Raleigh, N. C., in 1960 and for helping spread “Eyes on the Prize” throughout the South. As song leader for the famed Highlander Folk School (where Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks had attended workshops in the 1950s), Guy was on the front lines of the first sit-ins of the ’60s Civil Rights Movement (along with many others who today are still relatively unsung). His warm personality and quiet steadiness made him an ideal participant in that struggle. Yet throughout their lives, Guy and his wife Candie have been so self-effacing and so scrupulous about crediting others, that their own contributions have been largely overlooked. In addition to their participation in and invaluable documentation of the Civil Rights movement, they have also worked tirelessly organizing and advocating for voter literacy and worker health and safety issues. As performers and folklorists they have done as much as anyone to celebrate and preserve traditional music. Alan Lomax wrote that the Carawans, “instead of just writing books and making records, . . . instead of just singing, . . . have gone to the problem areas, to the face of the culture, to the creators, with patience, with love, with wisdom, [and] have helped them toward the realization of themselves and their cultural heritage”(Letter, 1982).

Guy Carawan (b. Los Angeles, 1927) is best known for introducing the song that became the anthem of the Civil Rights movement, “We Shall Overcome,” to the founding convention of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNNC) in Raleigh, N. C., in 1960 and for helping spread “Eyes on the Prize” throughout the South. As song leader for the famed Highlander Folk School (where Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks had attended workshops in the 1950s), Guy was on the front lines of the first sit-ins of the ’60s Civil Rights Movement (along with many others who today are still relatively unsung). His warm personality and quiet steadiness made him an ideal participant in that struggle. Yet throughout their lives, Guy and his wife Candie have been so self-effacing and so scrupulous about crediting others, that their own contributions have been largely overlooked. In addition to their participation in and invaluable documentation of the Civil Rights movement, they have also worked tirelessly organizing and advocating for voter literacy and worker health and safety issues. As performers and folklorists they have done as much as anyone to celebrate and preserve traditional music. Alan Lomax wrote that the Carawans, “instead of just writing books and making records, . . . instead of just singing, . . . have gone to the problem areas, to the face of the culture, to the creators, with patience, with love, with wisdom, [and] have helped them toward the realization of themselves and their cultural heritage”(Letter, 1982).

Although a Californian, Guy’s roots are Southern. His mother, from a socially prominent family in Charleston, S. C., was resident poet at Winthrop College. His father was a decorated World War I veteran from a modest rural background, who farmed tobacco in North Carolina and did asbestos contracting in California. Both Guy’s father and brother died from asbestosis, which doubtless spurred Guy’s interest in miner lung health and safety issues. Guy graduated from Occidental College in 1949 with a degree in mathematics and received an M.A. in sociology from UCLA, with a special interest in folklore. Always musical, in college and graduate school he took up guitar, banjo, and hammer dulcimer.

Through his friend and musical partner Frank Hamilton (who subsequently replaced Pete Seeger in the Weavers), Guy became part of a group of political progressives active in and around Los Angeles (many former members of People’s Songs), who believed in using folk songs as a vehicle for grass roots activism. Early on, Wayland Hand, professor of German and folklore at UCLA, warned Guy against mixing folk music and politics, saying that the Nazis had done this in Germany, but Guy’s faith in music as a way to galvanize social change never wavered.

In the early ’50s Guy and Frank moved to New York City, where the lively Washington Square folk music scene included Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, Eric Darling, and Woody Guthrie’s acolyte, Jack Elliot. There were musical parties at Tiny Robinson’s (Lead Belly’s niece), and Guy often served as driver to Sonny Terry, who was blind. In 1953, Guy and Frank Hamilton decided to take a road trip to see the South, “I wanted to see the farm where my father had grown up,” Guy explained. Jack Elliot insisted on joining them and though they at first accepted his presence somewhat reluctantly, his musical and busking skills were to prove extremely useful.

On Pete Seeger’s recommendation, the trio stopped for several weeks at Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tenn. In the late 1940s Highlander had been center of interracial CIO organizing in the South. Now, forced by red baiting to curtail its union activities, it had shifted its focus to adult literacy and voter registration. Highlander, an adult education center founded in 1932 by Don West and Myles Horton (a student of Reinhold Niebuhr) on the model of Bishop Grundtvig’s Danish Folk Schools, had a mission of empowering people to better themselves and society through individual and collective action. Music played a significant role in the Folk School program, which included singing and weekly dances. Union organizer Zilphia Horton, a gifted singer who was married to Myles, ran the music program. One of her favorite songs was then known as “We Will Overcome” a hymn she had learned in 1945 from Lucille Simmons, who had sung it during a prolonged strike by the Negro Food and Tobacco Workers’ Union in Charleston, S.C., as a valediction to end each day’s picketing. Zilphia used it to end meetings at Highlander; it was printed in union song books, and was also in Pete Seeger and Frank Hamilton’s repertoires.

Energized by his Southern tour, Guy returned to California where he resumed his studies and performing career. During a European tour in 1957 he stayed for a month in London with Alan Lomax, with whom he formed a life-long personal and professional relationship. (Later, Lomax would send Guy the Cantometrics handbook and tapes to get his opinion on the method.) That year Guy was one of a group of 40 Americans, including Peggy Seeger, who attended the Sixth World Youth and Student Festival in Moscow and then traveled on for a six-week trip to the People’s Republic of China, in defiance of State Department rules, resulting in the revocation of their passports.

In 1959, learning that Highlander needed a music coordinator, Guy offered his services: “I knew that Zilphia Horton had died and Myles was without anyone to do music there. So I called Myles and asked if I could be a volunteer. He said yes, but I would have to do some real work there. He said they needed a music program.” (Sing Out, 44 [3]: 50)

When he arrived, local conservatives were trying to shut the school down. There were frequent police raids on trumped-up charges of serving liquor without a license, among other things. Staff and students often found themselves in the Grundy County Jail, where they sang to keep up their spirits. During a raid, while they were being forced to sit for several hours in the dark, a young student spontaneously added the verse “We are not afraid, today” to “We Shall Overcome,” giving the song a tremendous moral immediacy. The singers made other changes — in rhythm and syncopation that impressed Guy deeply as well. Ultimately, the harassment forced the school to relocate to Knoxville.

Precisely how “We Will Overcome” became “We Shall Overcome” (parallel to another celebrated union song, “We Shall Not Be Moved”) is not known. Some credit the change to pioneer activist and adult literacy teacher Septima Clark, Highlander’s director of workshops and founder of Citizenship Schools throughout the South. In 1959 Guy was Clark’s driver and assisted her in setting up a Citizenship School on Johns Island, S.C. They used documents such as the U.S. Constitution and also lyrics of songs sung at Highlander as reading texts to teach people to fill out drivers’ license and voter registration forms. When Guy introduced the labor movement staple, “Keep Your Hand on the Plow, Hold On,” a local resident, Mrs. Alice Wine, told him, “I know a different echo. We sing ‘Keep your Eyes on the Prize’.” Guy liked this version and adopted it into his repertoire.

On that trip Guy attended the unique all-night Christmas services at Moving Star Hall, which featured a distinctive polyrhythmic a cappella African-American spiritual “shouting” Gullah tradition that went back to Colonial days. It was a transforming experience for Guy, who would revisit Johns Island often and who formed a lifelong friendship with the founding family of Moving Star Hall headed by Janey Hunter, herself a teacher and disseminator of Sea Island traditions.

The first months of 1960 saw the historic first lunch counter sit-in campaign, first in Greensboro, N.C., and then in Nashville. On April 1, during Highlander’s annual College Workshop, held that year in Nashville, Guy Carawan taught 83 students new ways to sing old songs, many of which he had heard sung in jail. On April 15, two hundred students who had assembled as a youth wing of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference at Shaw University in Raleigh, N.C., determined to form their own independent body, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). They invited Carawan to lead the singing, and he closed the first evening of the three-day conference with “We Shall Overcome.” Movement leader Rev. C. T Vivian, a lieutenant of Martin Luther King reminisced:

I don’t think we had ever thought of spirituals as movement material. When the movement came up, we couldn’t apply them. The concept has to be there. It wasn’t just to have the music but to take the music out of our past and apply it to the new situation, to change it so it really fit.…. The first time I remember any change in our songs was when Guy came down from Highlander. Here he was with this guitar and tall thin frame, leaning forward and patting that foot. I remember James Bevel and I looked across at each other and smiled. Guy had taken this song, “Follow the Drinking Gourd” — I didn’t know the song, but he gave some background on it and boom — that began to make sense. And, little by little, spiritual after spiritual began to appear with new words and changes: “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize, Hold On” or “I’m Going to Sit at the Welcome Table.” Once we had seen it done, we could begin to do it.(Interview, 1983, quoted in Sing For Freedom: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement Through Its Songs, 1990, p. 4.)

On April 19, Vivian invited Guy to “bring your guitar” to a demonstration protesting the bombing of the home of prominent black Nashville lawyer Z. Alexander Looby. Four thousand demonstrators marched to Nashville’s City Hall, where Guy led the singing of “We Shall Overcome” adding the verse, “We are not alone.” In what David Halberstam (in The Children, 1999) has called one of the Civil Rights movement’s finest hours, student leader Diane Nash got white Mayor Ben West to publicly agree that segregation was morally wrong: “And the people shouted with a great shout, so that the wall came down,” reads a plaque erected on the spot today. Among the demonstrators present was Guy’s future wife, Candie Anderson, one of a handful of young white students who had come to Fisk University to take a workshop in Gandhian non-violent direct action with the Rev. James Lawson, the leading theoretician of the movement. Candie, like Guy, was a Californian of Southern lineage and was already a veteran of the sit-in movement.

By the summer of 1960, Guy believed that the young African-American singers were better than he and that his instruments got in the way of their exciting a cappella style and he gracefully stepped back. His role would henceforth be to collect, record, and teach songs rather than to lead them. Using Highlander as their base, Guy and Candie (who were married in April of 1961) would visit friends and alumni from Highlander all over the South and document the ongoing Civil Rights movement.

Later that year Guy returned to the Sea Island Citizenship Program, and in February of 1961, the year of the Freedom Rides, he brought a group of Freedom Singers from Nashville and Montgomery to Carnegie Hall for a benefit concert for Highlander organized by Pete and Toshi Seeger. In 1962 they went to Albany, Ga., where Guy recorded Freedom in the Air, which was produced by Guy and Alan Lomax for SNCC on Vanguard Records.

In 1963 Guy and Candie moved to Atlanta to work more closely with SNCC. The movement’s focus was shifting primarily to voting rights, and in June the couple returned to Johns Island to help with voter registration. Now the parents of a young son, they decided to make the island their home. During their residence they set up the Sea Island Folk Festival and arranged for the Moving Star Hall Singers to tour as a formal group.

In the late ’60s the Carawans moved to Hellier, Ky., in the rural eastern Appalachians, to support the striking coal mine workers. Corrupt relations between politicians and the mining industry produced strip mining and, with it, health issues —black lung was common — along with poverty, and poor social services. Guy and Candie worked to help the miners improve their health and dignity through community organizing. They also began to record and study in depth the music of Appalachia. They then returned to California where Guy taught courses in Civil Rights, American folk life, and ran Appalachian field-study programs for four years at Pitzer College in Claremont.

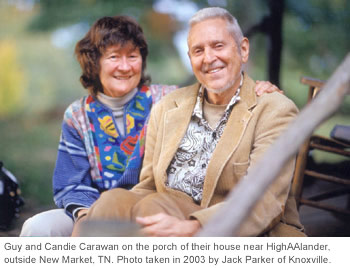

In 1972 the new Highlander moved from Knoxville to New Market, Tenn., in the Great Smokies, where the Carawans moved in 1975. In the ensuing years, Guy, Candie, their son Evan, and their daughter Heather have traveled to such political hot spots as Honduras and Nicaragua. Having explored Irish, Appalachian, and African-American music in the past, as well as the environmental and economic issues of Native Americans, the Carawans have most recently turned their attention to the music of the newer Latino populations in the South.

Guy recorded and released nearly thirty albums, often joined by Candie, herself a singer, and their son Evan, who also plays hammered dulcimer and mandolin. He has also produced albums for other performers (including the Stanley Brothers), written songs recorded by other performers (including Peter, Paul and Mary), and played guitar on albums for Shirley Collins’ first album and for Alan Lomax’s 1961 album of Texas songs, among others.

The Carawans have recently been the subject of a documentary film The Telling Takes Me Home (2005) by their daughter Heather. In 2006 Stanford University bestowed on them its King Award on the occasion of the inauguration of its newly expanded Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute.

Guy and Candie Carawans’ books include:

We Shall Overcome! Songs of the Southern Freedom Movement

Julius Lester, editorial assistant. Ethel Raim, music editor and design: Additional musical transcriptions: Joseph Byrd [and] Guy Carawan. New York: Oak Publications, 1963. .

Ain’t You Got a Right to the Tree of Life? The People of Johns Island, South Carolina —- their faces, their words and their songs.

Photographs by Robert Yellin. Music transcribed by Ethel Raim. Preface by Alan Lomax. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966. Reprint: University of Georgia Press, 1989. ISBN 0-82031-132-4

Freedom is a Constant Struggle Songs of The Freedom Movement, with Documentary Photographs.

Ethel Raim, music editor.New York: Oak Publications, 1968.

Voices from the Mountains: Life and Struggle in the Appalachian South (1975); Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1996. ISBN 0-82031-882-5

Sing for Freedom: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement through Its Songs

Bethlehem, PA: Sing Out Corp., 1990, 1992. ISBN 0-9626704-4-8 Incorporates We Shall Overcome! and Freedom is a Constant Struggle

Recordings include:

Songs with Guy Carawan. Folkways Records, FG 3544, 1950.

America at Play. CLP1174 1958. Children’s songs with Guy Carawan and Peggy Seeger.

Guy Carawan Sings: Something Old, New, Borrowed and Blue., Folkways Records, FG 3548, 1959.

Freedom in the Air: Albany Georgia. 1961-62. SNCC #101. Produced by Vanguard Records for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. Recorded by Guy Carawan. Produced by Guy Carawan and Alan Lomax. “Freedom In the Air . . . is a record of the 1961 protest in Albany, Georgia, when, two weeks before Christmas, 737 people brought the town nearly to a halt to force its integration. The record’s never been reissued and that’s a shame, as it’s a moving document of a community through its protest songs, church services, and experiences in the thick of the civil rights struggle.”—Nathan Salsburg, January 2007.

Birmingham, Alabama, 1963: Mass Meeting. Folkways Records, FD#5487, 1980. Includes Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Abernathy, and the Birmingham Movement Choir. Recorded by Guy Carawan in Birmingham, Al.

The Story of Greenwood, Mississippi. Folkways Records, FD#5593, 1965. Includes Robert Parris Moses, Fannie Lou Hamer, Medgar Evers, Dick Gregory. Recorded by Guy Carawan in Greenwood, MS.

Sea Island Folk Festival: Moving Star Hall Singers. Folkways Records, FS#3841, 1966. Includes Alan Lomax speaking at festival. Recorded and produced by Guy and Candie Carawan

Been in the Storm So Long: Spirituals, Shouts, Folk Tales and Children’s Songs of Johns Island, South Carolina. Folkways Records, FS#3842, 1967. Recorded and produced by Guy & Candie Carawan.

Freedom Now! Songs for a New America. With Candie Carawan. Plane Records, Germany, #55301, 1968.

Come All You Coal Miners. Rounder Records, #4005, 1974. Includes Nimrod Workman, Sarah Gunning, George Tucker, Hazel Dickens. Recorded by Roger and Lucy Phenix at Appalachian Music Workshop at Highlander Center, October 1972. Produced by Guy Carawan.

The Telling Takes Me Home. Cur Non Records, cnl 722, 1972

Sing for Freedom, Southwide Workshop. Folkways Records, FD#5488, 1980. Produced by Guy and Candie Carawan, Highlander Center. Recorded at the Gammon Theological Seminary in Atlanta, Ga., at a workshop with Freedom Singers, Birmingham Movement Choir, Georgia Sea Island Singers, Doc Reese, Phil Ochs, and Len Chandler.

They’ll Never Keep Us Down: Women’s Coal Mining Songs. Rounder Records, #4012, 1983. Includes Hazel Dickens, Sarah Gunning, Florence Reece, Phyllis Boyens, and the Reel World String Band. Dedicated to Sarah Gunning who died October 14, 1983. Produced by Guy and Candie Carawan for Rounder.

Hammer Dulcimer Music. With Evan Carawan. Flying Fish Records, FF 329, 1984.

Quotes:

Highlander was situated on some two hundred acres in Monteagle, Tennessee. In 1959 the local authorities had raided the school and arrested most members of its staff, including Guy Carawan; that began a two year legal battle on their part to close down the school by taking away its land. A series of charges, some bogus, some reflecting the prejudices of the time, were leveled at it: Highlander was holding integrated classes and integration was illegal in Tennessee . . . Horton was illegally selling beer without a license. In time the charge about integrated classes was dropped. But the overall campaign against Horton and his school was successful, the land was sold at public auction, and the Highlander people were forced to set up shop in Knoxville. . . . . The original Highlander land moved back and forth between different owners in different sales. Recently, in one of those wonderful ironies wherein places which were once scenes of violence in the South have now been designated as historical landmarks, some to the land was offered for sale again. The advertisement for the land in the local paper noted that his was a historically valuable piece of land, one “where the New South was born.”—David Halberstam, The Children, New York: Fawcett Books, 1999, pp. 207–208.

Now, Myles Horton is one of the most remarkable people of the twentieth century. . . . He built a central Highlander Folk School in the Appalachians (Grundy County, Tenn.) where he brought people together to discuss their fate. He didn’t tell them what to think — they told each other what they decided, and this center is where the Union Movement in the South began, where the voter registration movement in the South began. Rosa Parks, the black lady who somewhat single-handedly started the whole Civil Rights Movement by refusing to give up her seat on a segregated bus in downtown Montgomery, Alabama in 1955, was formed at Highlander. —Alan Lomax, interviewed by Arnold Rypens, 1994.

Letter to Alan prepared for the Folk Alliance Meeting in 1994

December 31, 1994

Dear Alan,

Candie and I are thinking about you as the year draws to a close. It’s a big challenge to put into words all the appreciation we feel for you after so many years of friendship. You are surely one of the few key people who have influenced our lives and work in the most major and dramatic way. We feel gratitude and love when we think of the years of support, generosity, and keen interest you have taken in our projects and our lives. Thank you, dear friend.

Long before I met you in person you were having an influence on me. Your books and the field recordings you and your father had put at the Library of Congress were much of the inspiration that got me into the study of folk song and folklore at UCLA with Wayland Hand. Your writings and recordings made the material come alive in a way that was absolutely irresistible. I had the good fortune to know and learn from Bess [Lomax Hawes] during those years, and she put me in touch with you when I traveled through London in 1957 on the way to the World Youth Festival in the Soviet Union and then on to China. Your personal generosity kicked in then. You let me stay in your London apartment learning about what you were doing and soaking up ideas about the power and richness of folk cultures; the link they can have to people’s social and political goals.

Once you had moved back to this country in 1960 and were living in New York City, I found my way to your apartment again and again over the years to talk with you about my own work — to play field recordings for you, show you photographs, discuss the importance of documentation, and also cultural organizing. You were always challenging — pushing me to think in new ways about what I was trying to do; you were always generous with your time and your knowledge.

Knowing about your work and the work of your family encouraged me to get a good Ampex tape recorder in 1959 and indeed to place myself in the heart of communities rich in cultural traditions. I first went to live on Johns Island, home of Mrs. Janie Hunter and Moving Star Hall, where Highlander was developing a literacy empowerment program. When Candie and I met in 1960, we began to follow the exciting events and locations of the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement — Albany, Birmingham, Jackson, Atlanta, Knoxville. And you would come to see us!

It meant a lot to me and to Candie also that you would come to see us in the Sea Islands and that you would participate in the cultural workshops we organized for civil rights workers in Mississippi and at Highlander in Knoxville. (We still remember how you taught two-year-old Evan to stamp his foot and shout, “Down with fascism!” when we were together on Johns Island.) Later you would also visit the Appalachian communities where we had been working in eastern Kentucky and Tennessee.

Many times when we needed it most, you gave public support to our work. You probably can’t even know how important that was to us. I know you continue to give support and encouragement to young people today. Your work with Cantometrics and with the Global Jukebox is creating a new generation of cultural activists.

For all this, and for being the creative and generous, inexhaustible person that you are, Candie and I send our profound thanks. Please stay well and healthy and please keep in good touch with us. We need you in our lives.

With much love,

Guy Carawan

Photo links: