Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads

John A. Lomax

New York: Sturgis and Walton, 1910, Cloth, 326 pp. [2nd Printing 1915] and London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1911, Cloth. New impression, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1920, Cloth, 326 pp. New edition, revised and enlarged by John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax.

New York: The Macmillan Company, 1937, Cloth, 431 pp. Third edition 1938. Reprint, Reprint Services Corp., March 1993, Cloth, 326 pp.

ISBN: 0781258901

The Book of Texas

John Avery Lomax and Harry Yandell Benedict

Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1916. 448 pp.

Read The Book of Texas

Songs of the Cattle Trail and Cow Camp

John A. Lomax with an introduction by William Lyon Phelps

New York: Macmillan, 1919. 189 pp. New Edition, illustrated with 78 drawings and sketches by famous Western artists (Frederic Remington, Charles Russell, Ross Santee and others). New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1950.

Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Leadbelly

John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax

New York: The Macmillan Company, 1936, Cloth, 242 pp.

Our Singing Country: A Second Volume of American Ballads and Folk Songs

John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax. Introduction, musical transcriptions and arrangements by Ruth Crawford Seeger.

New York: The Macmillan Company, 1941, Cloth, 416 pp. Reprinted, New York: Dover Publications, 2000, 464 pp, unabridged paperback edition. ISBN: 0486410897

American Folksong and Folklore: A Regional Bibliography

Alan Lomax and Sidney Robertson Cowell

New York, Progressive Education Association, 1942. Reprint, St. Clair Shores, Mich.: Scholarly Press, 1977. ISBN: 0403016150. Reprint, Temecula, CA: Reprint Services Corp., 1988, 62 pp. ISBN: 0781207673

Check-list of Recorded Songs in the English Language in the Archive of American Folk Song in July 1940

Alan Lomax. Washington, D.C.: Music Division, Library of Congress, 1942. Three volumes.

Freedom Songs of the United Nations

Alan Lomax and Svatava Jakobson. Washington, D.C.: Office of War Information, 1943.

Folk Song: USA

John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax. Melodies arranged by John A. and Alan Lomax. Piano accompaniment by Charles and Ruth Crawford Seeger.

New York: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, c.1947. Paperback edition, New York: Old Gold/Signet, 1956, 512 pp. Reprinted, New York: Signet Classics/New American Library, 1966. Reprinted, Trade Paperback, New York: New American Library (Plume Edition), 1975, 528 pp. Republished as Best Loved American Folk Songs, New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1947, Cloth, 407 pp.

Adventures of a Ballad Hunter

John A. Lomax

New York: The Macmillan Company, 1947, Cloth, 302 pp.

American Ballads and Folk Songs

John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax

New York: The Macmillan Company, New York, 1934, Cloth, 625 pp. Limited edition of 500 numbered and signed copies 1934. Second printing 1934. Ninth printing 1947, 14th printing 1957, 16th printing 1960, 19th printing 1965, 20th printing 1966, 21st printing 1967. Reprint Services Corp., December 1952, Cloth. ISBN: 9994494341. New York: Dover Publications, 1994, Paperback, 672 pp. ISBN: 0486282767

Mister Jelly Roll: The Fortunes of Jelly Roll Morton, New Orleans Creole and “Inventor of Jazz”

Alan Lomax. Drawings by David Stone Martin.

New York: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, 1950, Cloth, 318 pp. New York: Grove Press, 1950, Paperback, 302 pp. London: Cassell & Co. Ltd, 1952, Cloth. London: The Jazz Book Club/Cassell. 1956, Cloth, 296 pp. New York: The Universal Library/Grosset & Dunlap, 1967, Paperback, 318 pp. Paris: Editions Flammarion, 1964, 355 pp. Berkeley: University of California Press, Berkeley, 1973, Paperback, 368 pp. [Reprinted November 5, 2001. ISBN: 0520225309]. New edition with foreword by Kingsley Amis, London: Virgin Books, 1991, Paperback, 318 pp. New York: Pantheon Books, 1993, Paperback. ISBN: 0679740643

Harriet and Her Harmonium: An American adventure with thirteen folk songs from the Lomax collection

Alan Lomax. Illustrated by Pearl Binder. Music arranged by Robert Gill.

London: Faber and Faber, Ltd., 1955, Cloth, 48 pp. New York: A. S. Barnes, 1959.

Leadbelly: A Collection of World Famous Songs by Huddie Ledbetter

John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax, eds. Introduction by Alan Lomax. Hally Wood, Music Editor. Special note on Leadbelly’s 12-string guitar by Pete Seeger. New York: Folkways Music Publishers Company, 1959, Paperback, 80 pp.

The Rainbow Sign

Alan Lomax

New York: Duell, Sloan and Pierce, 1959, Cloth.

Folk Songs of North America

Alan Lomax. Melodies and guitar chords transcribed by Peggy Seeger. Piano arrangements by Mátyás Seiber and Don Banks. Illustrated by Michael Leonard. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co, 1960, Cloth, 623 pp. Paperback edition, New York: Doubleday/Dolphin, 1975, 619 pp + Index. ISBN: 0385037724

The Leadbelly Songbook

Moses Asch and Alan Lomax, Editors. Musical transcriptions by Jerry Silverman. Forward by Moses Asch.

New York: Oak Publications, 1962, soft cover, 96 pp. The ballads, blues, and folksongs of Huddie Leadbetter; illustrated with many drawings and some black and white photos. Articles: “Leadbelly” by Peter Seeger; “Leadbelly’s Legacy” by Frederic Ramsey, Jr.; “Leadbelly—King of the 12-String Guitar” by Charles E. Smith; “Midnight Special” by Woody Guthrie; and “Huddie Ledbetter” by Alan Lomax.

Hard-Hitting Songs for Hard-Hit People

Alan Lomax, Woody Guthrie, and Peter Seeger

New York: Oak Publications, 1967. Paperback edition, with a new afterword by Pete Seeger. Lincoln: Bison Books/University of Nebraska Press, November 1999, 376 pp. ISBN: 0803279914

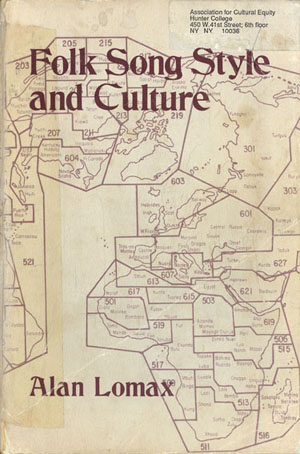

Folk Song Style and Culture

Alan Lomax, with contributions by the Cantometrics Staff: Conrad Arensberg, Edwin E. Erickson, Victor Grauer, Norman Berkowitz, Irmgard Bartenieff, Forrestine Paulay, Joan Halifax, Barbara Ayres, Norman N. Markel, Roswell Rudd, Monika Vizedom, Fred Peng, Roger Wescott, David Brown.

Washington, D.C.: Colonial Press Inc, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Publication no. 88, 1st Printing 1968, 2nd Printing 1971, Cloth, 363 pp. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1st Printing 1978, 2nd Printing 1994, Paperback, 363 pp. ISBN: 0878556400

3000 Years of Black Poetry

Alan Lomax and Raoul Abdul, Editors

New York: Dodd Mead Company, 1969. Cloth. Paperback edition, Fawcett Publications, 1971.

Cantometrics: An Approach to the Anthropology of Music: Audiocassettes and a Handbook

Alan Lomax

Berkeley: University of California Media Extension Center, 1976.

The Land Where the Blues Began

Alan Lomax

New York: Pantheon Books, 1993, Cloth. ISBN: 0679404244

Recipient of 1993 National Book Critics Award for Non-Fiction.

Brown Girl in the Ring: An Anthology of Song Games from the Eastern Caribbean

Alan Lomax (compiler), J. D. Elder (contributor), Bess Lomax Hawes (contributor) New York: Pantheon Books, 1997, Cloth, 256 pp, ISBN: 0679404538. New York: Random House, 1998, Cloth.

World Dance and Movement Style

Alan Lomax and Forrestine Paulay 1993. Unpublished manuscript.

All articles by Alan Lomax, unless otherwise noted. This list does not include published liner notes.

“‘Sinful’ Songs of the Southern Negro.” Southwest Review XIX, 2 (Winter 1934): 105–131.

“Haitian Journey: Search for Native Folklore.” Southwest Review XXIII, 2 (January 1938): 125–147.

Review of “Folk Songs of Mississippi and Their Background” by Arthur Hudson. Journal of American Folklore(1938): 211–213.

“Music in Your Own Back Yard.” The American Girl (October 1940): 5–7, 46, 49.

“List of American Folk Songs on Commercially Recorded Records.” First published in the Report of the Committee of the Conference on Inter-American Relations in the Field of Music, September 1940. Reprinted by the Library of Congress, 1942.

“Songs of the American Folk.” Modern Music 18 (Jan.–Feb. 1941): 137–139.

Preface to 14 Traditional Spanish Songs from Texas transcribed by Gustavo Duran. Washington, D.C: Pan-American Union, 1942.

“Of Men and Books.” Interview (on CBS) with Alan Lomax. Northwestern University on the Air, vol. 1, no. 18 (January 31, 1942).

“Reels and Work Songs.” In 75 Years of Freedom: Commemoration of the 75th Anniversary of the Proclamation of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, pp. 27–36.Washington, D.C.:Library of Congress, 1943.

“Mister Ledford and the TVA.” In Radio Drama in Action: Twenty-Five Plays of a Changing World. Erik Barnouw, ed., pp. 51–58. New York: Rinehart & Co., 1945.

“The Best of the Ballads.” Vogue (Dec. 1, 1946): 208, 291–296.

Lomax, Alan with Benjamin Botkin. “Folklore, American: Ten Eventful Years.” 1947 Encyclopedia Britannica: 359–367.

“America Sings the Saga of America.” New York Times Magazine, January 26, 1947.

“I Got the Blues.” Common Ground, vol. 8 (Summer 1948): 38–52.

“Tribal Voices in Many Tongues.” Saturday Review of Literature, May 28, 1949.

Foreword to A Garland of Mountain Song by Jean Ritchie. New York: Broadcast Music, Inc., 1953.

“Making Folk Music Available.” In Four Symposia on Folklore: Held at Midcentury Folklore Conference, Indiana University, July 21–August 4, 1950. Thompson, Stith, Editor. Pp. 155–62. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1953.

“Nuova ipotesi sul canto folkloristico italiano.” Nuovi Argomenti. Alberto Moravia and Alberto Carocci, eds. 17 / 18 (November/ February, 1955–56): 109–135.

“Skiffle: Why Is It So Popular?” Melody Maker, August 31, 1957: 3.

“Skiffle: Where Is It Going?” Melody Maker,September 7, 1957: 5.

“The ‘Folkniks’ and the Songs They Sing.” Sing Out! vol. 9, no. 1 (Summer 1959): 30–31. (Photo on cover.)

“Bluegrass Background: Folk Music With Overdrive.” Esquire, 52 (October 1959): 108.

“Folk Song Style.” American Anthropologist, vol. 61, no. 6 (December 1959): 927–54.

“Zora Neale Hurston: A Life of Negro Folklore.” Sing Out! vol. 10, no. 3 (Oct.–Nov. 1960): 12–13.

Calkins, Carol with Alan Lomax. “Getting to Know Folk Music.” House Beautiful (April 1960): 141, 205.

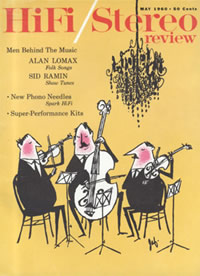

“Saga of a Folksong Hunter.” HI/FI Stereo Review (May 1960): 40–46.

“Folk Song Traditions Are All Around Us.” Sing Out! vol. 11, no. 1 (February–March 1961): 17–18.

“Aunt Molly Jackson: An Appreciation.” Kentucky Folklore Record, vol. 7, no. 4 (October–December 1961).

“The Adventure of Learning, 1960.” ACLS Newsletter, vol. 13 (February 1962).

“Song Structure and Social Structure.” Ethnology, vol. 1, no. 4 (January 1962): 425–452.

Foreword to Folk Songs of the Southern Appalachians by Jean Ritchie. New York: Oak Publications, 1965.

Lomax Alan, and Victor Grauer. “Cantometrics.” Journal of American Folklore Supplement (April 1964): 37–38.

Lomax, Alan, with Edith Crowell Trager. “Phonotactique du Chant Populaire.” L’Homme (January–April 1964): 1–55.

Preface to Ain't You Got a Right to the Tree of Life? The People of Johns Island, South Carolina — their faces, their words and their songs by Guy and Candie Carawan. Photographs by Robert Yellin. Music transcribed by Ethel Raim. (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966) Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1989.

“The Good and the Beautiful in Folksong.” Journal of American Folklore 317 (July–September 1967): 213–35.

“Special Features of the Sung Communication.” In Essays on the Verbal and Visual Arts, Proceedings of the 1966 Annual Spring Meeting, American Ethnological Society, 109–27. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1967.

“Song Styles: An Indicator of Popular Culture.” Public Opinion Quarterly 31 (1967): 469–70.

Lomax, Alan, Irmgard Bartenieff, and Forrestine Paulay. “Choreometrics: A Method for the Study of Cross-Cultural Pattern in Film.” Research Film vol. 6, no. 6, 1969.

“Africanisms in New World Negro Music.” In Research and Resources: Papers of the Conference on Research and Resources of Haiti,118–154. New York: Research Institute for the Study of Man, 1969.

“The Homogeneity of African-Afro-American Musical Style.” In Afro-American Anthropology: Contemporary Perspectives, Norman E. Whitten, Jr. and John F. Szwed, eds., 181–201. New York: Free Press, 1970.

“Choreometrics and Ethnographic Filmmaking: Toward an Ethnographic Film Archive.” Filmmaker’s Newsletter, vol. 4, no. 4 (February 1971).

“An Appeal for Cultural Equity.” The World of Music: Quarterly Journal of the International Music Council (UNESCO) in Association with the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation, vol. 14, no. 2, 1972.

“Brief Progress Report: Cantometrics-Choreometrics Projects.” Yearbook of the International Folk Music Council, 4, 1972: 142–45.

Lomax, Alan and Norman Berkowitz. “The Evolutionary Taxonomy of Culture.” Science, vol. 177 (July 21, 1972): 228–239.

“Cinema, Science, and Cultural Renewal.” Current Anthropology, vol. 14 (1973): 474–480.

“Singing: Folk and Non-Western Singing.” In New Encyclopedia Britannica: Macropedia, 15th Edition, 1974: XVI: 790–94.

“A Note on a Feminine Factor in Cultural History.” In Being Female: Reproduction, Power, and Change. Dana Raphael, ed. Pp. 131–37. The Hague: Mouton, 1975.

“Culture-Style: Factors in Face-to-Face Interaction.” In Organization of Behavior in Face-to-Face Interaction.Adam Kendon, et al., eds., pp. 457–74. The Hague: Mouton, 1975.

“People and Their Culture and the Pursuit of Happiness.” 1976 Festival of American Folklife: Smithsonian Institution National Park Service. Washington, D.C.: Office of Folklife Programs, Smithsonian Institution, 1976.

“Cross-Cultural Factors in Phonological Change.” Language in Society, vol. 2 (1973): 161–175.

Lomax, Alan, et al. “A Stylistic Analysis of Speaking.” Language in Society 6 (1977): 15–47.

“An Appeal for Cultural Equity: When Cultures Clash.” Journal of Communication. 27 (Spring 1977): 125–138.

Lomax, Alan with Conrad Arensberg. “A Worldwide Evolutionary Classification of Cultures by Subsistence Systems.” Current Anthropology, vol. 18 (1977): 659–708.

“Universals in Song.” World of Music: Journal of the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation (Berlin) in Association with the International Music Council (UNESCO) 19, nos. 1–2 (1977): 117–29. French translation: 131–41.

“Factors of Musical Style.” In Theory & Practice: Essays Presented to Gene Weltfish. Stanley Diamond, ed. Pp. 29–58. The Hague: Mouton, 1980.

“Folk Music in the Roosevelt Era.” Transcription of interview by Ralph Rinzler. Folk Music in the Roosevelt White House: A Commemorative Program, pp. 14–17. Washington, D.C.: Office of Folklife Programs, Smithsonian Institution, 1982.

Introduction to Never Without a Song: The Years and Songs of Jennie Devlin, 1865–1952 by Katharine D. Newman, pp. xii–xvi. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995.

Alan Lomax recorded several albums of his own performances of blues, ballads, and cowboy songs, singing and accompanying himself on guitar. These are indicated with an asterisk.

(Musicraft, 1939)

First commercial album of American folk songs, performed by Lead Belly. Produced by Alan Lomax. 1998 Grammy Hall of Fame Award recipient.

(Victor, 1940)

Performed by Woody Guthrie. Co-produced by Alan Lomax and R. P. Weatherald.

(Victor, 1940)

Songs of Texas prisons, performed by Lead Belly and the Golden Gate Quartet, recorded by Alan Lomax in Washington, D.C.

(Library of Congress, 1940)

,

An annotated survey of the field recordings in the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress, including Southern, Northern, and Western Euro-American songs and ballads; many types of African American songs from the United States and Bahamas; Mexican American songs and ballads; and songs and tunes from the Cajun country. This first recorded picture of a nation’s field recorded folk traditions was recorded by John A. Lomax, Alan Lomax, Herbert Halpert, and others, and edited by Alan Lomax. It was subsequently expanded by other collector/editors including Benjamin Botkin, William N. Fenton, Duncan Emrich, George Pullen Jackson, George Korson, Richard Waterman, Henrietta Yurchenco, and others. (Library of Congress, 1942)

Vol. 1: Anglo-American Ballads

Vol. 2: Anglo-American Shanties, Lyric Songs, Dance Tunes, and Spirituals

Vol. 3: Afro-American Spirituals, Work Songs, and Ballads

Vol. 4: Afro-American Blues and Game Songs. Bahaman Songs

Vol. 5: French Ballads and Dance Tunes. Spanish Religious Songs and Game Songs

(BBC, 1944)

A ballad opera produced in 1944 for the British Broadcasting Company. Produced by Alan Lomax, written by Elizabeth Lyttleton, directed by Roy Lockwood.

(Circle, 1947)

The first recorded biography of a jazz musician. The sessions were recorded by Alan Lomax at the Coolidge Auditorium of the Library of Congress between May and December of 1938. Only a few copies of the 54 twelve-inch master discs were made until 1947, when Circle Records pressed approximately 200 sets of 45 twelve-inch 78 rpm records, presented in 12 volumes. This edited version, culled from the May and June sessions, was later released on LP. 1980 Grammy Hall of Fame Award recipient. (Circle, 1947; reissued on LP by Circle, 1950, and Riverside, 1959)

(Brunswick/Decca, 1947–49)

In 1947 Alan Lomax became Director of Folk Music for Decca Records and edited a series of folk music albums, reissuing pre-war titles from the Decca, Vocalion, and Brunswick catalogs, and commissioning new recordings. Each release was comprised of four 10-inch 78 rpm discs.

Mountain Frolic

Listen to Our Story – A Panorama of American Ballads

Burl Ives: Ballads and Folk Songs (2 volumes)

Richard Dyer-Bennett: Twentieth Century Minstrel

John White: Ballads and Blues (2 volumes)

Cousin Emmy: Kentucky Mountain Ballads

Cowboy Dances

(Stinson, 1949)

Edited by Alan Lomax. Issued on four 10-inch 78 rpm discs.

(Columbia Records, 1954-1964)

First recorded overview of world music in 18 volumes of a projected 44. Compiled by Alan Lomax for Columbia Records’ Masterworks, 1955-1964.

Vol. 1: Ireland (Recorded and edited by Seamus Ennis and Alan Lomax)

Vol. 2: French Africa (Recorded by Henri Lhote, Andre Schaeffner, and Gilbert Rouget; edited by Schaeffner and Rouget)

Vol. 3: England (Recorded and edited by Peter Kennedy and Alan Lomax)

Vol. 4: France (Recorded and edited by Cl. Marcel-Dubois and Maguy Andral)

Vol. 5: Australia & New Guinea (Recorded and edited by A.P. Elkin)

Vol. 6: Scotland (Recorded and edited by Alan Lomax)

Vol. 7: Indonesia (Recorded and edited by Jaap Kunst)

Vol. 8: Canada (Recorded and edited by Marius Barbeau)

Vol. 9: Venezuela (Recorded and edited by Juan Liscano)

Vol. 10: British East Africa (Recorded and edited by Hugh Tracey)

Vol. 11: Japan, The Ryukyus, Formosa, and Korea(Recorded and edited by Genjiro Masu)

Vol. 12: India (Recorded and edited by Alain Danielou)

Vol. 13: Spain (Recorded and edited by Alan Lomax)

Vol. 14: Yugoslavia (Edited by Alan Lomax, recorded by Peter Kennedy)

Vol. 15: Northern and Central Italy (Recorded and edited by Alan Lomax and Diego Carpitella)

Vol. 16: Southern Italy and the Islands (Recorded and edited by Alan Lomax and Diego Carpitella)

Vol. 17: Bulgaria (Recorded and edited by A.L. Lloyd)

Vol. 18: Romania (Recorded and edited by Tiberiu Alexandru)

(Columbia Masterworks, 1955)

The recordings of a field survey made in 1952-1953.

Vol. 1: Andalusia

Vol. 2: Majorca & Ibiza

Vol. 3: Jerez & Seville

Vol. 4: Majorca & Aragon

Vol. 5: Granada & Seville

Vol. 6: The Spanish Basques

Vol. 7: Eastern Spain & Valencia

Vol. 8: Galicia

Vol. 9 : Asturias & Santander

Vol. 10: Castille

Vol. 11: Leon & Extremadura

(Decca, 1956)

A four song 7-inch ep of the Ramblers skiffle group, featuring Alan Lomax, Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger, Shirley Collins, Sandy Brown, John Cole, Bryan Daley, Jim Bray and Alan Sutton.

(Decca, 1957)

Featuring Alan Lomax and the Ramblers, Lonnie Donegan, and Ken Colyer among others.

(HMV, 1958)

A fifteen-track LP of Lomax performing traditional ballads with accompaniment by British blues pioneer Alexis Korner (under the pseudonym “Nick Wheatstraw”) and Guy Carawan and production support from an uncredited Guy Carawan.

(Nixa, 1958)

Featuring Alan Lomax with Peggy Seeger, Guy Carawan, John Cole and Sammy Stokes; engineered by Joe Meek.

(Kapp, 1958)

(Nixa, 1958)

Four song 7-inch ep of Lomax accompanied by Dave Lee’s Bandits. (Nixa Jazz Today

Series)

(Tradition, 1958)

Sung by Lomax with accompaniment by Guy Carawan on guitar and banjo and John Cole on harmonica.

(Tradition, 1958)

Sung by Lomax with accompaniment by Guy Carawan on guitar and banjo and John Cole on harmonica.

(Tradition, 1958)

Traditional music from across Italy, recorded by Alan Lomax and Diego Carpitella in 1954 and 1955.

(Tradition, 1959)

Traditional Scottish music collected from native folksingers and folk musicians by Alan Lomax, Calum McLean, and Hamish Henderson in 1950 and 1951. Their publication led to the founding of the Scottish folk song archive at the School for Scottish Studies.

(Tradition, 1959)

Recordings made with the first portable tape machine at Parchman Farm, the Mississippi State Penitentiary.

(United Artists, 1959)

Alan Lomax Presents Folk Song Festival at Carnegie Hall. Featuring Jimmy Driftwood, Memphis Slim, Muddy Waters, and the Stoney Mountain Boys.

(United Artists, 1959)

Alan Lomax presents Folk Songs From The Blue Grass. Featuring Earl Taylor and His Stoney Mountain Boys.

(Atlantic, 1960)

First stereo field recordings of American folk music, made in 1959. (Reissued as “Sounds of the South” 4-CD set, 1993)

Vol. 1: Sounds of the South

Vol. 2: Blue Ridge Mountain Music

Vol. 3: Roots of the Blues

Vol. 4: White Spirituals

Vol. 5: American Folk Songs for Children

Vol. 6: Negro Church Music

Vol. 7: The Blues Roll On

(Prestige, 1960)

More 1959-1960 stereo recordings from the white and black South.

Vol. 1: Georgia Sea Islands, Vol. I

Vol. 2: Georgia Sea Islands, Vol. II

Vol. 3: Ballads and Breakdowns from the Southern Mountains

Vol. 4: Banjo Songs, Ballads and Reels from the Southern Mountains

Vol. 5: Deep South… Sacred and Sinful

Vol. 6: Folk Songs from the Ozarks

Vol. 7: All Day Singing from “The Sacred Harp”

Vol. 8: The Eastern Shores

Vol. 9: Bad Man Ballads

Vol. 10: Yazoo Delta Blues and Spirituals

Vol. 11: Southern White Spirituals

Vol. 12: Honor the Lamb: The Belleville A Cappella Choir of the Church of God and Saints in Christ

(Caedmon, 1961)

A survey of folk music of the British Isles recorded in the field and produced by Alan Lomax and Peter Kennedy, 1950-1958.

Vol. 1: Songs of Courtship

Vol. 2: Songs of Seduction

Vol. 3: Jack of All Trades

Vol. 4: The Child Ballads 1

Vol. 5: The Child Ballads 2

Vol. 6: Sailormen and Servingmaids

Vol. 7: Fair Game and Foul

Vol. 8: A Soldiers Life for Me

Vol. 9: Songs of Ceremony

Vol. 10: Songs of Animals and Other Marvels

(SNCC, 1962)

A documentary on the 1961 civil rights protest in Albany, Georgia. Produced by Alan Lomax and Guy Carawan. (SNCC, 1962)

(Kapp, 1963)

(Electra, 1964)

A three-record set of an edited selection of Lomax’s 1940 oral history sessions with Guthrie. (Reissued by Rounder, 1989.)

(Folkways, 1965)

Edited by Alan Lomax and Carla Bianco.

(Rounder, 1971)

A single LP of songs and interviews culled from Lomax’s 1937 oral history sessions with Aunt Molly.

(Ethnic Folkways, 1972)

(Ethnic Folkways, 1972)

(New World, 1977)

(New World, 1977)

(New World, 1977)

(Topic, 1977)

Recorded in Galax for the Library of Congress, 1941.

(Swallow, 1987)

(Warners New Media, 1992)

Produced by Carl Sagan. Includes music that Alan Lomax selected for the Voyager spacecraft mission.

Read more about the project.

(Rounder, 2003)

In 1947 Alan Lomax recorded bluesmen Big Bill Broonzy, Memphis Slim, and Sonny Boy Williamson on a Presto disc recording machine at Decca Studios in New York City after they had given concert at Town Hall. In a session of candid oral history and song, the three artists explain the origin and nature of the blues. The interviews were issued in a fictionalized form in Common Ground (1948) under the title “I Got the Blues,” but they were deemed so controversial that their album release was delayed for ten years. When United Artists finally issued them on LP as Blues In the Mississippi Night in 1959, Lomax used pseudonyms to protect the artists and their families. (United Artists, 1959; reissued by Rykodisc, 1990 and Rounder, 2003.)

To Hear Your Banjo Play

Directed by Willard Van Dyke, script by Alan Lomax. A production of the Office of War Information, 1945. (30 minutes)

Oss! Oss! Wee Oss! – May Day In Padstow

May Day festivities in Cornwall’s ctoastal village of Padstow are dedicated to the “Old ‘Oss” and his attendants in a remarkable community ritual with roots dating to pre-Christian times. Directed and scripted by Alan Lomax, produced by Peter Kennedy, cinematography by George Pickow, and sound by Jean Ritchie. Shot on Kodacolor film in 1951 with the support of the English Folk Dance and Song Society. (60 minutes)

Ballads, Blues, and Bluegrass

An intimate song swap filmed in Lomax’s apartment, spontaneously arranged after a 1961 Clarence Ashley concert at Carnegie Hall, produced by the Friends of Old-Time Music. Crowding into Lomax’s West 3rd Street walk-up were Ashley, Roscoe Holcomb, Doc Watson, Jean Ritchie, Jack Elliott, Peter LaFarge, the New Lost City Ramblers, Memphis Slim, and Willie Dixon. Directed by Alan Lomax, filmed by George Pickow, sound by Jean Ritchie. (60 minutes)

MUSIC FROM NEWPORT

Performances from the 1966 Newport Folk Festival, including Skip James, Howlin' Wolf, Son House, Rev. Pearly Brown, Bukka White, Ed & Lonnie Young, Clark Kessinger, Jimmy Driftwood, Kilby Snow, the Coon Creek Girls, Canray Fontenot, Bois Sec Ardoin, Almon and Virginia Manes, Tex Logan, Grant Rogers, and others. (All are 60 minutes)

Devil Got My Woman

Delta Blues / Cajun Two Step

Billy In the Lowgrounds: Old-Time Music from Newport

RHYTHMS OF EARTH: THE MOVEMENT STYLE AND CULTURE SERIES

These four films illustrate the pioneering work of Alan Lomax and Forrestine Paulay in Choreometrics, a comparative method of studying the relationship of dance style to human geography. The films employ ethnographic footage filmed in many parts of the world to show how aspects of movement vary with aspects of social structure. Written, directed, and produced by Alan Lomax and Forrestine Paulay. CINE Golden Eagle Awards, Dance Film Festival Awards, Margaret Mead Film Festival honorees. The series was published by the UC Berkeley Extension Center for Media and Independent Learning.

Dance and Human History, 1976

This introduction to Choreometrics illustrates important scales by which dance can be measured, then utilizes the scales to classify dance into ethnographic regions. Also analyzes the influence of economic productivity and the division of labor between the sexes on dance. (60 minutes)Step Style, 1980

Focuses on leg and foot movements in dance and their relation to cultural patterns, work movements, and sports. (30 minutes)Palm Play, 1980

People in some parts of the world dance with their palms completely covered or turned in while others openly present their palms to their partners. This film offers a novel explanation of the symbolism and cultural determinants of the universal dance element of palm gestures. (30 minutes)The Longest Trail, 1986

This exploration of the dance traditions of the American Indian shows more than 50 Native American dances and recounts one of the great human adventures: the settlement of the New World by peoples coming across the Bering Strait land bridge thousands of years ago. (30 minutes)

TELEVISION

The Song Hunter

Written and hosted by Alan Lomax, directed by David Attenborough. (BBC Television, 1953-1954)

Dirty Old Town

Script and direction by Alan Lomax. (Granada Television, 1956)

The Golden Isles - Cradle of American Song

Alan Lomax and Accent series host John Ciardi visit the Georgia Sea Island Singers, hear their singing, watch their dancing, and interview Bessie Jones. (Accent, CBS TV, 1962)

AMERICAN PATCHWORK SERIES

From 1978 to 1985 Alan Lomax traveled the American South and Southwest with a television crew to document regional folklore with deep historical roots. From the resulting 400 hours of footage came the five-program series American Patchwork, which aired on PBS in 1991. (All are 60 minutes)

The Land Where the Blues Began, 1979

Alan Lomax, John Bishop, and Worth Long explored the enduring African-American performance traditions of the Mississippi Delta. Featuring bluesmen R. L. Burnside and Jack Owens; tall-tale tellers; fife and drum bands; diddley-bow players; and former prisoners, railroad workers, and roustabouts singing field hollers, work chants, and levee camp songs. Winner of the Blue Ribbon in the American Film Festival, 1985. Produced with the support of Mississippi Educational Television, the film was later edited for the American Patchwork series broadcast version for PBS.

“The Land Where The Blues Began” by John Bishop. Filmmakers Monthly, XIII(9), July 1980.

Jazz Parades

A celebration of New Orleans’ musical culture — from its piano bars and barrelhouses to brass bands and street parades, with their colorful, riotous, and symbolic second lines, in which the community plays an essential part in the performance. Archival film footage, photographs, interviews with and performances by the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, the Dirty Dozen Brass Band, Mardi Gras Indians, and Danny Barker tell the story of the New Orleans tradition.

Cajun Country

Cajun Country

The bayous of Louisiana have combined French, German, West Indian, native American and hillbilly ingredients into a unique cultural gumbo. Cajun Country investigates the Cajuns’ roots in Western France, visits their cattle drives, horse races, and fais do-dos in rural Louisiana, and listens to the salty tales and raunchy songs of its black, white, and Indian music-makers.

Appalachian Journey

Alan Lomax travels through the hills and hollers of the Southern Appalachians investigating the songs, dances, and religious rituals of the descendents of the Scotch-Irish frontiers-people who have made the mountains their home for centuries. Preachers, fiddlers, moonshiners, cloggers and square dancers recount the good times and the hard times of mountain life. Performances by Tommy Jarrell; Janette Carter; Ray and Stanley Hicks; Frank Proffitt, Jr.; Sheila Kay Adams; and Ray Fairchild, the man reputed to be the fastest banjo-picker in the world.

Dreams and Songs of the Noble Old

Dreams and Songs of the Noble Old

An examination of the talents and wisdom of elderly musicians, singers, and story-tellers, who perform not for fame or fortune but to preserve and share their culture. Stories told by Janie Hunter (80 years old) of Johns Island, S.C.; ballads sung by ex-coal miner and union organizer Nimrod Workman (91), of Chatteroy, W.V.; fiddle tunes and tales of moonshining and feuds from Tommy Jarrell (83) of Toast, N.C.; and footage from the Alabama Sacred Harp Convention in Fyffe, Alabama, in which people of all ages gather to sing old-time shape-note hymnody.

Order the Patchwork films on DVD through Media Generation.

"Saga of a Folksong Hunter - A Twenty-year Odyssey with Cylinder, Disc and Tape"

-Alan Lomax. HiFi Stereo Review, May 1960.

To the musicologists of the 21st century our epoch may not be known by the name of a school of composers or of a musical style. It may well be called the period of the phonograph or the age of the golden ear, when, for a time, a passionate aural curiosity overshadowed the ability to create music. Tape decks and turntables spun out swing and symphony, pop and primitive with equal fidelity; and the hi-fi LP brought the music of the whole world to mankind's pad. It became more important to give all music a hearing than to get on with the somewhat stale tasks of the symphonic tradition. The naked Australian mooing into his djedbangari and Heifetz noodling away at his cat-gut were both brilliantly recorded. The human race listened, ruminating, not sure whether there should be a universal, cosmopolitan musical language, or whether we should go back to the old-fashioned ways of our ancestors, with a different music in every village. This, at least, is what happened to me.

To the musicologists of the 21st century our epoch may not be known by the name of a school of composers or of a musical style. It may well be called the period of the phonograph or the age of the golden ear, when, for a time, a passionate aural curiosity overshadowed the ability to create music. Tape decks and turntables spun out swing and symphony, pop and primitive with equal fidelity; and the hi-fi LP brought the music of the whole world to mankind's pad. It became more important to give all music a hearing than to get on with the somewhat stale tasks of the symphonic tradition. The naked Australian mooing into his djedbangari and Heifetz noodling away at his cat-gut were both brilliantly recorded. The human race listened, ruminating, not sure whether there should be a universal, cosmopolitan musical language, or whether we should go back to the old-fashioned ways of our ancestors, with a different music in every village. This, at least, is what happened to me.

In the summer of 1933, Thomas A. Edison's widow gave my father an old-fashioned Edison cylinder machine so that he might record Negro tunes for a forthcoming book of American ballads. For us, this instrument was a way of taking down tunes quickly and accurately; but to the singers themselves, the squeaky, scratchy voice that emerged from the speaking tube meant that they had made communicative contact with a bigger world than their own. A Tennessee convict did some fancy drumming on the top of a little lard pail. When, he listened to his record, he sighed and said, "When that man in the White House hear how sweet I can drum, he sho' gonna send down here and turn me loose." Leadbelly, then serving life in the Louisiana pen, recorded a pardon-appeal ballad to Governor O. K. Allen, persuaded my father to take the disc to the Governor, and was, in fact, paroled within six months.

I remember one evening on a South Texas sharecropper plantation. The fields were white with cotton, but the Negro families wore rags. In the evening they gathered at a little ramshackle church to sing for our machine. After a few spirituals, the crowd called for Blue- "Come on up and sing-um your song, Blue." Blue, a tall fellow in faded overalls, was pushed into the circle of lamplight and picked up the recording horn. "I won't sing my song but once," he said. "You've got to catch it the first time I sing it." We cranked up the spring motor, dropped the recording needle on the cylinder, and Blue began –

Poor farmer, poor farmer,

Poor farmer, they git all the farmer makes . . .

Somebody in the dark busted out giggling. Scared eyes turned toward the back of the hall where the white farm owner stood listening in the shadows. The sweat popped-out on Blue's forehead as he sang on . . .

His clothes is full of patches, his hat is full of holes,

Stoopin' down, pickin' cotton, from off the bottom bolls,

Poor farmer, poor farmer . . .

The song was a rhymed indictment of the sharecropping system, and poor Blue had feared we would censor it. He had also risked his skin to record it. But he was rewarded. When the ghostly voice of the Edison machine repeated his words, someone shouted, "That thing sho' talks sense. Blue, you done it this time!" Blue stomped on his ragged hat. The crowd burst into applause. When we thought to look around, the white manager had disappeared. But no one seemed concerned. The plantation folk had put their sentiments on record!

As Blue and his friends saw, the recording machine can be a voice for the voiceless, for the millions in the world who have no access to the main channels of communication, and whose cultures are being talked to death by all sorts of well-intentioned people – teachers, missionaries, etc – and who are being shouted into silence by our commercially bought and paid for loudspeakers. It took me a long time to realize that the main point of my activity was to redress the balance a bit, to put sound technology at the disposal of the folk, to bring channels of communication to all sorts of artists and areas.

Meanwhile, I continued to work as a folklorist. That is – out of the ocean of oral tradition I gathered the songs and stories that I thought might be of some use or interest to my own group – the intellectuals of the middle class. I remember how my father and I used to talk, back in those far off days twenty five years ago, about how a great composer might use our stuff as the basis for an American opera. We were a bit vague about the matter because we were Texans and had never seen a live composer.

I kept on talking about that American-opera-based-on-folk-themes, until one year the Columbia Broadcasting System commissioned a group of America's leading serious composers to write settings for the folk songs presented on my series for CBS's School of the Air. The formula was simple. First you had the charming folk tune, simply and crudely performed by myself or one of my friends. Then it was to be transmute by the magic of symphonic technique into big music, just as it was supposed to have happened with Bach and Haydn and the boys. This was music education.

I recall the day I took all our best field recordings of John Henry to one of our top-ranking composers, a very bright and busy man who genuinely thought he liked folk songs. I played him all sorts of variants of John Henry, exciting enough to make a modern folk fan climb the walls. But as soon as my singer would finish a stanza or so, the composer would say, "Fine- Now let's hear the next tune." It took him about a half-hour to learn all that John Henry, our finest ballad, had to say to him, and I departed with my treasured records, not sure whether I was more impressed by his facility, or angry because he had never really listened to John Henry.

When his piece was played on the air, I was unsure no longer. My composer friend had written the tunes down accurately, but his composition spoke for the Paris of Nadia Boulanger, and not for the wild land and the heart-torn people who had made the song. The spirit and the emotion of John Henry shone nowhere in this score because he had never heard, much less experienced them. And this same pattern held true for all the folk-symphonic suites for twenty boring weeks. The experiment, which must have cost CBS a small fortune, was a colossal failure, and had failed to produce a single bar of music worthy of association with the folk tradition. As the years have gone by, I have found less and less value in the symphonizing of folk song. Each tradition has its own place in the scheme of mankind's needs, but their forced marriage produces puny offspring. Perhaps our American folk operas will come from the sources we least expect, maybe from some college kid who has learned to play the five-string banjo and guitar, folk-style, or from some yet unknown hillbilly genius who develops a genuine American folk-style orchestra.

In the early days, when we were taking notes with our recording machine for that imaginary American opera or for our own books, we normally recorded only a stanza or two of a song. The Edison recorder of that first summer was succeeded by a portable disc machine that embossed a sound track on a well-greased aluminum platter; but the surface scratch was thunderous, and besides, we were too hard pressed for money to be prodigal with discs. Now, the recollection of all the full-bodied performances we cut short still gives me twinges of conscience. Even more painful is the thought that many of the finest things we gathered for the Library of Congress are on those cursed aluminum records; they will probably outlast the century, complete with acoustic properties that render them unendurable to all but the hardiest ears.

This barbaric practice of recording sample tunes did not continue for long, for our work had found a home in the Archive of American Folk Song, established in the Library of Congress by the late Herbert Putnam, then Librarian, and there were funds for plenty of discs. By then, we had also come to realize that the practice among the folk of varying the tune from stanza to stanza of a long song was an art both ancient in tradition and subtle in execution- one which deserved to be documented in full. So it was that we began to record the songs in their entirety.

Learning that the Russians were writing full-scale life histories of their major ballad singers, I then began to take down lengthy musical biographies of the most interesting people who came my way. Thus, Leadbelly's life and repertoire became a book‑the first folksinger biography in English, and unhappily out of print a year after it was published. Jelly Roll Morton, Woody Guthrie, Aunt Molly Jackson, Big Bill Broonzy and a dozen lesser-known singers all set down their lives and philosophies for the Congressional Library microphones. In that way I learned that folk song in a context of folk talk made a lot more sense than in a concert hall.

By 1942 the Archive of American Folk Music had become the leading institution of its kind in the world, with several thousand songs on record from all over the United States and parts of Latin America. With Harold Spivacke, Chief of the Music Division, I planned a systematic regional survey of American folk music. We were lending equipment and some financial aid to the best regional collectors. We had our own sound laboratory, had published a series of discs with full notes and texts which was greeted with respect and admiration by museums and played on radio networks the world over- though little in the United States. By teaching our best discoveries to talented balladeers like Burl Ives, Josh White and Pete Seeger, many hitherto forgotten songs began to achieve national circulation. Even music educators began to give serious thought to the idea of using American folk songs as an aid toward the musical development of American children- properly arranged with piano accompaniment and censored, of course.

Then came the day when a grass-roots Congressman, casually inspecting the Congressional Library's Appropriation Bill, noted an item of $15,000 for further building up the collection for the Archive of American Folk Music. This gentleman thereupon built up a head of steam and proceeded to deliver an impassioned speech, demanding to know by what right his constituents' money was being spent "by that long-haired radical poet, Archibald MacLeish, running up and down our country, collecting itinerant songs."

A shocked House committee rose to this national emergency. It not only cut the appropriation for the Archive out of the bill, but along with it a million dollars earmarked for the increase of the entire Library. Our national Library would have to get along without the purchase of books, technical journals and manuscripts for a year- but at least that poet would also have to stop doing whatever he was doing with those "itinerant songs."

I was hardly the most popular man in the Library of Congress during the ensuing week. My name had not been mentioned in Committee, but the blame for what happened fell on me- for my noisy round objects had never fitted into the quiet rectangular world of my librarian colleagues. For a few days I walked down those marble corridors in a pool of silence. Then logs were rolled and the million dollars for the Library were restored, apparently, though, with the understanding that the folk song Archive should get none of it ever. To the best of my knowledge, no further government funds since that day have been appropriated for the pursuit of "itinerant" songs. Although the Archive has continued to grow, thanks to gifts and exchanges, it has ceased to be the active center for systematic collecting that we so desperately need in this unknown folksy nation of ours.

To the best of my knowledge, I say, because when it became plain that the Archive was no longer to be a center for field trips, I sadly shook the marble dust of the Library off my shoes, and have paid only occasional visits there since. However, once the field recording habit takes hold of you, it is hard to break. One remembers those times when the moment in a field recording situation is just right. There arises an intimacy close to love. The performer gives you his strongest and deepest feeling, and, if he is a folk singer, this emotion can reveal the character of his whole community. A practiced folk song collector can bring about communication on this level wherever he chooses to set up his machine. Ask him how he does this, and he can no more tell you than a minister can tell you how to preach a great sermon. It takes practice and it takes a deep need on the part of the field collector- which the singer can sense and want to fulfill.

I swore I would never touch another recording machine after I left the Library of Congress; but then, somehow, I found myself the owner of the first good portable tape machine to become available after World War Two. Gone the needle rasp of the aluminum disc; gone the worry with the chip and delicate surface of the acetates. Here was a quiet sound track with better fidelity than I had imagined ever possible; and a machine that virtually ran itself, so that I could give my full attention to the musicians.

I rushed the machine and myself back to the Parchman (Mississippi) Penitentiary where my father and I had found the finest, wildest and most complex folk singing in the South. The great blizzard of 1947 struck during the recording sessions, and the convicts stood in the wood yard in six inches of snow, while their axe blades glittered blue in the wintry light and they bawled out their ironic complaint to Rosie, the feminine deity of the Mississippi Pen–

Ain't but the one thing I done wrong,

I stayed in Mississippi just a day too long.

Come and get me, Rosie, an' take me home,

These life-time devils, they won't leave me alone.

Although my primitive tape recorder disintegrated after that first trip, it sang the songs of my convict friends so faithfully that it married me to tape recording. I was then innocent of the nervous torments of tape splicing and of the years I was to spend in airless dubbing studios in the endless pursuit of higher and higher "fi" for my folk musicians. The development of the long-playing record- a near perfect means for publishing a folk song collection- provided a further incentive; for one LP encompasses as much folk music as a normal printed monograph and presents the vital reality of an exotic song style as written musical notation never can. At a summer conference dealing with the problemsof international folk lore, held in 1949, I proposed to my technically innocent colleagues that we set up a committee to publish the best of all our folk song findings as a series of LPs that would map the whole world of folk music. Exactly one person- and he was a close friend of mine- voted in favor of my proposal.

The myopia of the academics was still a favorite topic of mine, when one morning, a few weeks later, I happened to meet Goddard Lieberson, President of Columbia Records, in a Broadway coffee shop. His reaction to my story was to agree on the spot that it would be an interesting idea to publish a World Library of Folk Music on LP- if I could assemble it for him at a modest cost. Out of my past there then arose a shade to lend a helping hand in my project.

The first song recorded for the Library of Congress, Leadbelly's Goodnight Irene, had just become one of the big popular hits of the year; and it seemed to me, in all fairness, that my share of the royalties should be spent on more folk song research. Thus, within ten days of my chat with Lieberson, I was sailing for Europe with a new Magnecord tape machine in my cabin and the folk music of the world as my destination. I loftily assured my friends at the dock that, by collaborating with the folk music experts of Europe and drawing upon their archives, the job would take me no more than a year. That was in October of 1950.

It was July, 1958 before I actually returned home with 20 of the promised 40 tapes complete. Seventeen LPs in all, each one capsuling the folk music of as many different areas and edited by the foremost expert in his particular field, were released on Columbia; and eleven LPs on the folk music of Spain were edited for and released by Westminster. "Irene" had long since ceased to pay my song-hunting bills. As a matter of fact, for several years I had supported my dream of an international "vox humana" for several years by doing broadcasts on the British Broadcasting Corporation's Third Programme. I had also become a past master in wangling my recorder and accompanying bales of tapes through customs, as well as by a dyed-in-the-wool European tyrant in the dining room of a continental hotel.

There were several reasons why my efficient American planning of 1950 had gone awry. For one thing, only a few European archives of folksong recordings existed which were both broad enough in scope and sufficiently "hi-fi" to produce a good hour of tape that would acceptably represent an entire country. For another, not every scholar or archivist responded with pleasure to my offer to publish his work in fine style and with a good American royalty. There was the eminent musicologist who demanded all his royalties (whatever they were to be) in advance because he did not trust big American corporations (he was a violent anti-communist as well). Yet another was opposed to release his recordings prior to publication of his own musical analysis of them. Others, as curators of state museums, were tied down by red tape. In one instance, despite unanimous agreement in favor of my recording project, it took a year for the contract to be approved by the Department of Fine Arts and then a year more for the final selection of the tracks to be made. As for the folklorists of Soviet Russia, ten years of letter writing has yet to bring an answer to my invitation for them to contribute to the "World Library" project.

I simply could not afford to go everywhere myself. Much "World Library" material had to be gathered by correspondence- and that in a multitude of languages. So a huge file of letters accompanied me wherever I went, and inevitably there were a number of painful misunderstandings. One well-meaning gentleman hired a fine soprano to record his country's best folk songs. Another scholar, from the Antipodes and more anthropologist than musician, sent me beautiful tapes of hitherto unknown music- all recorded consistently at wrong speeds, but with no information to indicate the variations. The most painful incident, and one which still gives me nightmares, concerns a lady who, on the strength of my contract, made a six month field trip and then sent me tapes of such poor technical quality that all the sound engineers in Paris were unable to put them right. I had no choice but to return the tapes, and the lady soon found herself with no choice but to leave her native land to escape her creditors.

Despite such problems, the job as a whole went smoothly, for the Library of Congress Archive records had preceded me and made friends for me everywhere. My European colleagues must have enjoyed leading their provincial American co-worker through land after unknown land of music, and though I had sworn to stay away from field recording and to act merely in the capacity of editor, the temptation posed by unexplored or inadequately recorded areas of folk music in the heart of the continent from which our civilization sprang was simply too much for me.

It so happened that mine was the first high-fidelity portable tape recorder to be made available in Europe for folk song collecting. So I soon put it to work in the interest of the music that my new-found colleagues loved. The winter of 1950 I spent in Western Ireland, where the songs have such a jewelled beauty that one soon believes, along with the Irish themselves, that music is a gift of the fairies. The next summer, in Scotland, I recorded border ballads among the plowmen of Aberdeenshire, and later the pre-Christian choral songs of the Hebrides- some of them among the noblest folk tunes of Western Europe.

In the summer of 1953, I was informed by Columbia that publication of my series depended on my assembling a record of, Spanish folk music; and so, swallowing my distaste for EL Caudillo and his works, I betook myself to a folklore conference on the island of Mallorca with the aim of finding myself a Spanish editor. At that time, I did not know that my Dutch traveling companion was the son of the man who had headed the underground in Holland during the German occupation; but he was recognized at once by the professor who ran the conference. This man was a refugee Nazi, who had taken over the Berlin folk song archive after Hitler had removed its Jewish chief and who, after the war, had fled to Spain and was there placed in charge of folk music research at the Institute for Higher Studies in Madrid. When I told him about my project, he let me know that he personally would see to it that no Spanish musicologist would help me. He also suggested that I leave Spain.

I had not really intended to stay. I had only a few reels of tape on hand, and I had made no study of Spanish ethnology. This, however, was my first experience with a Nazi and, as I looked across the luncheon table at this authoritarian idiot, I promised myself that I would record the music of this benighted country if it took me the rest of my life. Down deep, I was also delighted at the prospect of adventure in a landscape that reminded me so much of my native Texas.

For a month or so I wandered erratically, sunstruck by the grave beauty of the land, faint and sick at the sight of this noble people, ground down by poverty and a police state. I saw that in Spain, folklore was not mere fantasy and entertainment. Each Spanish village was a self-contained cultural system with tradition penetrating every aspect of life; and it was this system of traditional, often pagan mores, that had been the spiritual armor of the Spanish people against the many forms of tyranny imposed upon them through the centuries. It was in their inherited folklore that the peasants, the fishermen, the muleteers arid the shepherds I met, found their models for that noble behavior and that sense of the beautiful which made them such satisfactory friends.

It was never hard to find the best singers in Spain, because everyone in their neighborhood knew them and understood how and why they were the finest stylists in their particular idiom. Nor, except in the hungry South, did people ask for money in exchange for their ballads. I was their guest, and more than that, a kindred spirit who appreciated the things they found beautiful. Thus, a folklorist in Spain finds more than song; he makes life-long friendships and renews his belief in mankind.

The Spain that was richest in both music and fine people was not the hot-blooded gypsy South with its flamenco, but the quiet, somber plains of the west, the highlands of Northern Castile, and the green tangle of the Pyrenees where Spain faces the Atlantic and the Bay of Biscay. I remember the night I spent in the straw but of a shepherd on the moonlit plains of Extramadura. He played the one-string vihuela, the instrument of the medieval minstrels, and sang ballads of the wars of Charlemagne, while his two ancient cronies sighed over the woes of courtly lovers now five hundred years in the dust. I remember the head of the history department at the University of Oviedo, who, when he heard my story, cancelled all his engagements for a week so that he might guide me to the finest singers in his beloved mountain province. I remember a night in a Basque whaling port, when the fleet came in and the sailors found their women in a little bar, and, raising their glasses began to sing in robust harmony that few trained choruses could match.

Seven months of wine‑drenched adventure passed. The tires on my Citroen had worn so smooth that on one rainy winter day in Galicia I had nine punctures. The blackhatted and dreadful Guardia Civil had me on their lists- I will never know why, for they never arrested me. But apparently, they always knew where I was. No matter in what Godforsaken, unlikely spot in the mountains I would set up my gear, they would appear like so many black buzzards carrying with them the stink of fear- and then the musicians would lose heart. It was time to leave Spain. I had seventy-five hours of tapes with beautiful songs from every province, and, rising to my mind's eye, a new idea- a map of Spanish folk song style- the old choral North, the solo- voiced and oriental South, and the hard-voiced modern center, land of the ballad and of the modern lyrics. Spain, in spite of my Nazi professor, was on tape. I now looked forward to a stay in England which would give me a chance to air my Iberian musical treasures over the BBC.

In the days before the hostility of the tabloid press and the Conservative Party had combined to denature the BBC's Third Programme, it was probably the freest and most influential cultural forum in the Western world. If you had something interesting to say, if the music you had composed or discovered was fresh and original, you got a hearing on the "Third." Some of the best poets in England lived mainly on the income gotten from their Third Programme broadcasts, which was calculated on the princely basis of a guinea a line. Censorship was minimal- and if a literary work demanded it, all the four-letter anglo-saxon words were used. You could also be sure, if your talk was on the "Third," that it would be heard by intelligent people, seriously interested in your subject.

My broadcast audience in Britain was around a million, not large by American buckshot standards, but one really worth talking to. I could not discuss politics- my announced subject being Spanish folk music- but I was still so angry about the misery and the political oppression I had seen in Spain that my feelings came through between the lines and my listeners were- or so they wrote me- deeply moved. At any rate, the Spanish broadcasts created a stir and the heads of the Third Progamme then commissioned me to go to Italy to make a similar survey of the folk music there.

That year was to be the happiest of my life. Most Italians, no matter who they are or how they live, are concerned about aesthetic matters. They may have only a rocky hillside and their bare hands to work with, but on that hillside they will build a house or a whole village whose lines superbly fit its setting. So, too, a community may have a folk tradition confined to just one or two melodies, but there is passionate concern that these be sung in exactly the right way.

I remember one day when I set up the battered old Magnecord on a tuna fishing barge, fifteen miles out on the glassy, blue Mediterranean. No tuna had come into the underwater trap for months, and the fishermen had not been paid for almost a year. Yet, they bawled out their capstan shanties as if they were actually hauling in a rich catch, and at a certain point slapped their bare feet on the deck, simulating exactly the dying convulsions of a dozen tuna. Then, on hearing the playback, they applauded their own performance like so many opera singers. Their shanties- the first, I believe, ever to be recorded in situ- dealt exclusively with two subjects: the pleasures of the bed which awaited them on shore, and the villainy of the tuna fishery owner, whom they referred to as the pesce cane (dog-fish or shark).

In the mountains above San Remo I recorded French medieval ballads, sung as I believe ballads originally were, in counterpoint and in a rhythm, which showed that they were once choral dances. In a Genoese waterfront bar I heard the longshoremen troll their five-part tralaleros- in the most complex polyphonic choral folk style west of the Caucasusone completely scorned by the respectable citizens of the rich Italian port. In Venice I found still in use the pile-driving chants that once accompanied the work of the battipali, who long ago had sunk millions of oak logs into the mud and thus laid the foundation of the most beautiful city in Europe. High in the Apennines I watched villagers perform a three-hour folk opera based on Carolingian legends and called maggi (May plays)- all this in a style that was fashionable in Florence before the rise of opera there. These players sang in a kind of folk bel canto which led me to suppose that the roots of this kind of vocalizing as we know it in the opera house may well have had their origin somewhere in old Tuscany. Along the Neapolitan coast I discovered communities whose music was North African in feeling- a folk tradition dating back to the Moorish domination of Naples in the ninth century. Then, a few miles away in the hills, I heard a troupe of small town artisans, close kin to Shakespeare's Snug and Bottom, wobble through a hilarious musical lark straight out of the commedia del' arte.

The rugged and lovely Italian peninsula turned out, in fact, to be a museum of musical antiquities, where day after day. I turned up ancient folk song genres totally unknown to my colleagues in Rome. By chance I happened to be the first person to record in the field over the whole Italian countryside, and I began to understand how the men of the Renaissance must have felt upon discovering the buried and hidden treasure of classical Greek and Roman antiquity. In a sense, I was a kind of musical Columbus in reverse. Nor had I arrived on the scene a moment too soon.

Most Italian city musicians regard the songs of their country neighbors with an aversion every bit as strong as that which middle-class American Negroes feel for the genuine folk songs of the Deep South. These urban Italians want everything to be "bella,"- that is, pretty, or prettified. Thus (in the fashion of most of our own American so-called folk singers active in the entertainment field) the professional purveyors of folk music in Italy leave out from their performances all that is angry, disturbing or strange. And the Radio Italiana, faithful in its obligations to Tin Pan Alley, plugs Neapolitan pop fare and American jazz day after day on its best hours. It is only natural that village folk musicians, after a certain amount of exposure to the TV screens and loudspeakers of RAI should begin to lose confidence in their own tradition.

One hot day, in the office of the program director of Radio Roma, I lost my temper and accused him of being directly responsible for destroying the folk music of his own country, the richest heritage of its kind in Western Europe. At this really charming fellow I directed all the hopeless rage I felt at our so-called civilization- the hard sell that is wiping the world slate clean of all non-conformist culture patterns.

To my surprise, he took up my suggestion that a daily folksong broadcast be scheduled for noon, when the shepherds and farmers of Italy are home and at leisure. I then wrote a romantic article for the radio daily, called The Hills Are Listening, in which I envisioned my friends and neighbors taking new heart as they heard their own voices coming out of the loudspeakers. Then, months later, I learned to my embarrassment that my piece had finally seen publication in an obscure learned journal and that the broadcasts were put on late in the evening, well after working class Italy is in bed- and on Italy's "Third Program" to boot, which only a small minority of intellectuals ever listen to.

When are we going to realize that the world's richest resource is mankind itself, and that of all his creations, his culture is the most valuable? And by this I do not mean culture with a capital "C"- that body of art which the critics have selected out of the literate traditions of Western Europe –but rather the total accumulation of man's fantasy and wisdom, taking form as it does in images, tunes, rhythms, figures of speech, recipes, dances, religious beliefs and ways of making love that still persist in full vitality in the folk and primitive places of our planet. Every smallest branch of the human family at one time or another has carved its dreams out of the rock on which it has lived- true and sometimes pain- filled dreams, but still wholly appropriate to their particular bit of earth. Each of these ways of expressing emotion has been the handiwork of generations of unknown poets, musicians and human hearts. Now, we of the jets, the wireless and the atom blast are on the verge of sweeping completely off the globe what unspoiled folklore is left, at least wherever it cannot quickly conform to the successmotivated standards of our urban- conditioned consumer economy. What was once an ancient tropical garden of immense color and variety is in danger of being replaced by a comfortable but sterile and sleep- inducing system of cultural super-highways- with just one type of diet and one available kind of music.

It is only a few sentimental folklorists like myself who seem to be disturbed by this prospect today, but tomorrow, when it will be too late- when the whole world is bored with automated mass-distributed video-music, our descendants will despise us for having thrown away the best of our culture.

The small triumph referred to in the early part of this article- the growing recognition of the importance of folk and sometimes primitive music on long-playing records- is a good step in the right direction. But it is only a first step. It still remains for us to learn how we can put our magnificent mass communication technology at the service of each and every branch of the human family. If it continues to be aimed in only one direction- from our semi-literate western, urban society to all the "underdeveloped" billions who still speak and sing in their many special languages and dialects, the effect in the end can only mean a catastrophic cultural disaster for us all.