Thinking about my father

by Anna Lomax Wood

“Neighborhood investigation shows him to be a very peculiar individual in that he is only interested in folk lore music, being very temperamental and ornery. …. He has no sense of money values, handling his own and Government property in a neglectful manner, and paying practically no attention to his personal appearance. … He has a tendency to neglect his work over a period of time and then just before a deadline he produces excellent results.” (from the FBI file on Alan Lomax, 1940–1980)

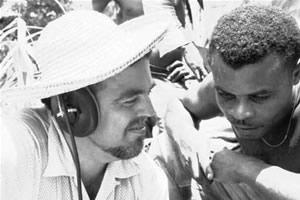

In an age that decries romanticism, Alan Lomax stands out as an enormously romantic figure. “I thought of Alan as a Minotaur — half man, half supernatural — who defied life as we know it,” wrote one of his old friends, Bill Ferris. Alan was proudest of his driving — his thousands of miles and days down nameless roads seeking out the jewels of the human spirit. He is most famous for his work in the penitentiaries, plantations, and lonely farms of the Mississippi Delta, where he returned no less than seven times between 1933 and 1985 to listen, observe, fraternize, and record night after night, year after year; but he repeated this feat with astounding results in hundreds of obscure places in the U.S., the Caribbean, Europe, and North Africa. Jelly Roll Morton, Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Muddy Waters, and the Reverend Gary Davis were only a few of the many geniuses, famous and obscure, who were in reality telling us the true story of our country over Alan’s microphone. The sympathy, connoisseurship, and technical avant-gardism he poured into his work in every platform — from the interview to the printed page, concert stage, commercial disc, and scholarly article — yielded some of the most passionate and intimate documents of any era, which might have been lost but instead led to the ecumenical vision of the world’s music we have today. But more than this, what Alan Lomax had in mind was the renewal of the forgotten springs of human creativity.

In the 1930s and early ‘40s Alan and his equally temperamental father, folklorist John A. Lomax — who was among the first collectors to recognize the value of African American music as a sui generis art form and one of the richest sources of indigenous American culture — helped to develop the Library of Congress’ Archive of American Folk Song as a national resource, recording thousands of songs and oral histories in their original settings, throughout the South, the Northeast, Lake States, Midwest, Bahamas, and Haiti. Among Alan’s earliest collaborators and lifelong friends were Zora Neale Hurston, Stetson Kennedy, Jerome Wiesner, Nicholas Ray, Charles and Ruth Crawford Seeger, Henry and Sidney Cowell, Román and Svatava Pirkova Jakobson, John Henry Faulk, Margaret Mead, and Edmund Carpenter. He gave young Pete Seeger his first job, searching for commercially recorded gems of regional Americana at the Library of Congress in 1938 and later at Decca Records, where they rescued some from the reject pile and tossed others “down the airshaft.” Alan introduced Woody Guthrie, Aunt Molly Jackson, Lead Belly, Josh White, Burl Ives, Pete Seeger, Sonny Terry, and Jean Ritchie on national radio and in concerts, records, and books, igniting careers and folk song movements. With the Seegers, Tillman Cadle, Aunt Molly, and Guy and Candie Carawan, and others he helped to bring the vital element of protest in folk songs into the union struggle, the Wallace campaign, and the Civil Rights Movement.

In the 1950s, Alan Lomax collected throughout Great Britain, Ireland, Italy, and Spain — dogged there by Franco’s political police. He enriched national folklore archives, created interest in indigenous folk music, and compiled for Columbia Records the first world music anthology. To the delight of British audiences, Lomax and Peter Kennedy shook up the normally staid BBC, putting fresh talent from the “field” live on the air each week with wildly unpredictable results. And just before the Queen’s radio address on Christmas Day 1957, native and immigrant folk musicians sang in the holiday on live hookup from the Hebrides, Glasgow, Cork, Manchester, Wales, Cornwall, Sussex, and London’s East End in an unrehearsed extravaganza.

In essence, the many facets of Lomax’s career were an expression of his belief in what he called “cultural equity” — the idea that the expressive traditions of all local and ethnic cultures should be equally valued as representative of the multiple forms of human adaptation on earth. After 1960 he devoted himself to comparative research on world music and dance with collaborators from musicology, anthropology, dance, and linguistics. This culminated in the early ‘90s with the Global Jukebox, a monumental attempt to organize and synthesize the findings of anthropology and musicology that evoked relationships between expressive style, human geography, and long-standing patterns of subsistence and social life.

Reverence for language, and the desire to become a full-fledged writer, permeates Lomax’s every composition — letters, speeches, grant proposals, and off-the-cuff remarks — to say nothing of his compressed song descriptions, private diaries, and longer works. Like Levi-Strauss, he was a writerly ethnographer and was proud of having pioneered the oral musical biography. Mister Jelly Roll (his biography of the famed New Orleans jazz composer) and his award-winning memoir, The Land Where the Blues Began, exemplify his admiration and respect for the artistry of oral historians, raconteurs, and poets.

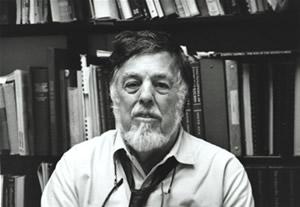

Alan Lomax was a flamboyant, protean personality, difficult to pigeonhole. He was loved for his warm enthusiasms, generosity, loyalty, and intense interest in people, hated for his high-handedness, his outbursts of Calvinistic fury, and admired and envied for the breadth of his ideas and accomplishments. To many he was a father figure, though he chafed under the role. Alan had enormous respect for women and their achievements, but he feared their power and never settled down. As a Texan he was smooth, genial, yet extremely touchy — a contrarian and a rebel, painfully empathetic with the troubles of others. Though sustained by an essentially sanguine temperament, he was often afflicted with gloom and loss of confidence. As a result of childhood illness Lomax suffered a partial loss of hearing, yet he had an incomparable ear for vocal music. A massive stroke forced him to retire in 1996 and live under the care of his family. He died on July 19, 2002, at the age of 87.

“We have an overarching goal — the world of manifold civilizations animated by the vision of cultural equity.”