by Peter Stone

You blow in this end of the trombone and sound comes out the other end and disrupts the cosmos.

- Roswell Rudd

Although firmly rooted in Dixieland, the exuberant improvised sound of free jazz pioneer Roswell Rudd's trombone is decidedly modern and, indeed, goes "further ahead than anyone else has reached" (Nat Hentoff). As well as performing, Rudd is also a trained musicologist who worked extensively with Alan Lomax and his Cantometrics research team, an association that informed and facilitated his collaborative forays in World Music in recent decades.

Although firmly rooted in Dixieland, the exuberant improvised sound of free jazz pioneer Roswell Rudd's trombone is decidedly modern and, indeed, goes "further ahead than anyone else has reached" (Nat Hentoff). As well as performing, Rudd is also a trained musicologist who worked extensively with Alan Lomax and his Cantometrics research team, an association that informed and facilitated his collaborative forays in World Music in recent decades.

Born November 17, 1935, in Sharon, Connecticut, Roswell Hopkins Rudd grew up in Connecticut and in upper New York State. His life-long fascination with improvisation arguably began in childhood, while listening to his grandmother, who, when directing her Methodist church choir, would, "on the chorus of the hymns, . . . improvise a descant super libre in a high, pneumatic voice and just soar over the entire choir" (Francis Davis, "White Anglo-Saxon Pythagorean," from Bebop and Nothingness: Jazz and Pop at the End of the Century [New York: Schirmer Books, 1996]). His father, an amateur drummer, held jam sessions at home and avidly collected recordings of Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet, Eddie Condon, Bix Beiderbecke, and Woody Herman from the 1920s, '30s, and '40s. "My favorite was Spike Jones," Rudd told critic John Ephland. Everything "goes back to the jam sessions," which Rudd likens to the sound of people talking and laughing with one another (see Tomas Pena, "Conversation with Roswell Rudd.")

Rudd studied mellophone in elementary school,from age eleven, French horn, and after a few years, began to teach himself trombone. He heard his first live jazz band in the 1940s - he recalls hearing stride pianist James P. Johnson, who died in 1945. From 1950 to 1954, Rudd and friends from the Hotchkiss School in Connecticut would to travel into New York City to hear Louis Armstrong live (not surprisingly, Armstrong was his first major influence). Charlie Parker at Jazz at the Philharmonic overwhelmed him, and other performers (among them Ellington), whom he heard at Birdland, the Half Note, and Eddie Condon's, also informed his musical tastes.

At Yale he belonged to Eli's Chosen Six, a traditional Dixieland sextet that played the fraternity house circuit in Yale and elsewhere (see Geoffrey Himes, "Roswell Rudd: Song Styles of a Planet"(Jazztimes, January/February 2006). They made two recordings, one for Columbia Records called Eli's Chosen Six. In 1960, after graduating with a major in musicology and theory, he moved to New York City, where he played in various traditional bands, and worked as composer, arranger, bandleader, musicologist, and teacher. He also performed with, among others, Eddie Condon.

Although some commentators feel that Rudd bypassed Bebop, leaping almost directly from Dixieland to Free Jazz in the late 1950s, Rudd himself disagrees: Bebop was and always will be [italics Rudd's] a big challenge, and there are people like Slide Hampton who can play the trombone like a piano . . . . There is a European harmonic theoretical foundation and an African modal rhythmic foundation in bop. . . . [It] is a music conservatory for the world. Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker took all of us to school! . . . The most exciting thing for me about Eli's Chosen Six was the last three choruses of a Dixieland tune, where everyone stands up and goes off the rails to see what can happen. In bop one person improvises, supported by a rhythm section. In Free Jazz, the number of people playing was unimportant - it was spontaneous call and response. . . . I grew up in collective improvisation, and that was what I heard with Archie Shepp and Ornette Coleman (Pena). That's what got me into the music of the 1960s, . . . because it was the same thing: everyone started soloing at once and just went for the sound. I call it free counterpoint, the sending out of sound from one person to another and back again until you create an acoustic togetherness. I heard that on those old Dixieland recordings and I heard that in the new jazz of the '60s (Himes, 2006).

Thelonious Monk's recordings had been out for about seven years when Rudd first heard them in the mid-1950s. Whereas Parker's improvisational style was virtuosic velocity incarnate, Monk's was "anti-velocity, with plenty of space" (Pena). Monk's clarity, intelligence, emotion, and ability to develop logical improvisation out of his own compositions appealed to Rudd - and opened him up to a better understanding of Parker and his contemporaries.

In 1960 Rudd met Steve Lacy, who became his longtime friend and colleague. A soprano saxophonist, Lacy began his career playing in traditional Dixieland style but had also played with Monk. Intrigued by Monk's songs, they realized that they could capture his sound with soprano sax, trombone, double bass, and drums.

Rudd also worked in a more modern vein with pianist Herbie Nichols, who became a kind of mentor, until his death from leukemia in 1963 at the age of 44. Nichols likewise had worked in Dixieland and Swing but composed in a more progressive style. The music of both Monk and Nichols - strangely moving, quirky, and iconoclastic - appealed to Rudd, in whose own music humor is often just beneath the surface.

In 1961 Rudd made his first recording in New York City, performing with the New York City R & B with Cecil Taylor on piano; Buell Neidlinger on bass; and Billy Higgins on drums. In the ensuing years, Rudd performed with various combinations of "experimental" musicians.

In 1962, he joined Free Jazz trumpeter Bill Dixon's group. In free-form jazz, collective improvisation takes place, not so much over a pre-conceived harmonic skeleton but rather on contrapuntally generated melodic riffs, each performer "feeding" the other. Dixon's 1964 concert series, October Revolution in Jazz, engendered the Jazz Composers Orchestra, formed in 1965 by Austrian composer and trumpeter Michael Mantler and keyboardist Carla Bley. Its 1968 double album Communications featured Taylor; trumpeter Don Cherry; tenor saxes Pharoah Sanders and Gato Barbieri; guitarist Larry Coryell; and Rudd (the orchestra would later commission Rudd's Numatik Swing Band in 1973).

Rudd was part of Steve Lacy's 1963 School Days Quartet - which played only Monk tunes - with bassist Henry Grimes and drummer Denis Charles. In 1964, he performed on the soundtrack of Michael Snow's New York Eye and Ear Control with Don Cherry; tenor sax Albert Ayler; alto, then tenor sax Danish-Congolese John Tchicai; and bassist Gary Peacock. In the following years, Rudd would join up with other luminaries in the forefront of experimentation: pianist Gil Evans; trumpeter Clark Terry; bassist Charlie Haden; vibraphonist, pianist, and musicologist Karl Berger (who, with Ornette Coleman, formed the Creative Music Studio in Woodstock, NY); and especially, tenor sax Archie Shepp, who became a close friend. Rudd played with Shepp's quartet until 1967. Then in 1968 Rudd formed Primordial Group - with Karl Berger and alto saxophonists Lee Konitz and Robin Kenyatta - which often morphed into larger ensembles.

Most important - because he was beginning to write jazz still connected to the collective improvisation of his Dixieland roots and would be able to do a lot of free improvisation with them - Rudd founded the New York Art Quartet in 1963 with Tchicai, bassist Lewis Worrell, and drummer Milford Graves. It lasted only until 1965, when Tchicai returned to Denmark.

The improvisatory freedom Rudd sought was given great impetus by his connection with Alan Lomax. Beginning in April 1964 for about three decades on and off Rudd worked as staff musicologist for Lomax's Cantometrics and subsequent Cantometrics Teaching Tapes and Global Jukebox projects. "It was very intense, nine to five, five days per week; and it was difficult integrating that into the things I wanted to do in New York. Sometimes I would work for a year and sometimes I would have to lay off and do something else around New York City" (Pena).

As part of the Lomax team, Rudd analyzed world folk song performances from some 2,500 field recordings, the results of which appeared in the book, Folk Song Style and Culture (Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1968). In 1969, he selected and prepared materials for an Atlantic Records LP, Black Encyclopedia of the Air (based on the Lomax team's 1966 radio project) of the same name) and was soundtrack consultant for the People of the Pacific Hall at the American Museum of Natural History. In addition, Rudd narrated and helped prepare Alan Lomax's set of teaching tapes: Cantometrics, An Approach to the Anthropology of Music: Audiocassettes and a Handbook (Berkeley: University of California Media Extension Center, 1976). "The work I did with Alan Lomax . . . gave me more chops and more ears," he told Pena.

In the '70s and '80s Rudd recorded Trickles, Blown Bone, and Flexible Flyer, which featured Lacy and singer Sheila Jordan, among others. He also taught after-school music programs for the Police Athletic League in Brooklyn and was a faculty member of Jazz Interactions School for Young Musicians in New York City.

From 1972 to 1976, Rudd was a Visiting Lecturer at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. He recounts:

I would take the train up to Bard in the middle of the week, teach classes from the afternoon into the evening, then get up the next day, teach some more and take the train home. . . . [T]here were many students who wanted to write their own music, play jazz and study the history of jazz. . . . I also offered a course in World Music and conducted an improvisation work shop and jam sessions. (Pena)]

In 1976, Alan Lomax wrote a letter of recommendation for Rudd to Charles D. Danforth, the Chairman of the Division of Arts and Humanities of the University of Maine at Augusta. Rudd, Alan explained, had worked with him as musicologist on Cantometrics project for two years, co-analyzing some 4,000 performances of world folk music and, after a leave spent pursuing his career, had returned in 1969 for two more years to resume his analyses and to work on a set of instructional tapes:

by means of which any person . . . could learn the distinctive features and distribution of classical folk and popular music styles across the world. Rudd continued to work periodically when his schedule permitted, adding to the teaching tapes, coding more song performances, assisting in the transcription of archive materials. . . . He is one of a handful of persons who has experienced the whole world of music from all commercially available and privately recorded sources. (Letter, July 29, 1976 in the Alan Lomax Archives)

Rudd was hired by the University of Maine, where from 1976 to 1982, he taught prescribed music courses and explained improvising systems from around the world - Indian ragas, flamenco, sambas, etc. But his attempts to integrate his professional performing career with his university duties created tension within the faculty and he was not granted tenure. He then moved to the Woodstock area of the Catskillswith his wife Moselle Galbraith, and son Chris. Rudd also had a grown son, Greg, from his first marriage to Marilyn Schwartz, and Moselle had two daughters by a former marriage. Periodically, Rudd returned to the Lomax project, working from 1984 to 1985 with Lomax and Forrestine Paulay on a study of American popular music and dance, The Urban Strain, which used Cantometrics and Choreometrics to analyze twentieth-century commercially made film and recordings. The study documented the crossovers between African- and European-derived performance modes that had emerged in every decade, generating additional innovative expressive systems in unusual combinations, for which new descriptors were required. It came to a close in 1994.

In 1995, Rudd recorded Wozzek's Death (with tenor saxophonist Allen Lowe), based on Georg Buchner's unfinished play, Woyzeck (but totally unrelated to Alban Berg's opera). He returned to the music of his mentor in The Unheard Herbie Nichols, Volumes 1 & 2 (1996-97), with music that Nichols had not recorded before. The instrumentation - trombone, guitar, and drums - reflected Rudd's interest in unexpected sound combinations, but the albums met with a mixed critical reception.

The year 1998, when Rudd recorded the track "The Year was 1503" on the Ab Baars Trio album Four, inaugurated a new phase in his life. The album credit reads: "Roswell Rudd represented by Verna Gillis/Soundscape." Rudd's had known Verna Gillis since her graduate student days Goddard College, where he supervised her Master's Thesis. She subsequently received a Ph. D. in Ethnomusicology in from Union Institute and University, Cincinnati, taught at Brooklyn College and Carnegie Mellon University, produced of recordings of African music, and worked as presenter on WBAI radio.

In 1979, Gillis and her husband Bradford Graves, a sculptor and saxophonist, established Soundscape, a performance space located on 52nd Street and 10th Avenue in Manhattan, where Gillis presented pioneering concerts of World Music and jazz, including Afro-Caribbean and African pop. There were also poetry readings by Archie Shepp and performances by Sun Ra and Roswell Rudd, among others. Gillis produced the program Interpretations of Monk for WBAI in February 1979. A 1981 concert version of this show at Wollman Auditorium, Columbia University, featured Rudd and pianists Barry Harris, Muhal Richard Abrams, Anthony Davis, and Mal Waldron; Don Cherry, Steve Lacy, and Charlie Rouse on horns; bass Richard Davis; and Ed Blackwell and Ben Riley on drums. The recording of the concert (a four-CD set on Gillis's Soundscape Series) includes Amiri Baraka reciting his poetry and commentary by Gillis, Nat Hentoff, and Stanley Crouch. Gillis also devoted herself to developing the careers of such performers King Sunny Ade and Youssou N'dour. Soundscape endured until 1984, when Bradford Graves suffered a heart attack.

Gillis and Graves had property in Kerhonksen, N.Y., near where Rudd lived, and Verna had transformed the former train station in nearby Accord, into a performance arts and community center, not unlike Soundscape. In 1998, Bradford Graves died, and not long afterwards Rudd's wife Moselle was incapacitated by a stroke and entered a nursing home; Verna and Roswell turned to each other and began a personal and professional partnership.

As recognition began to come to Rudd, he continued to record and experiment. Monk's Dream, an album with Steve Lacy was nominated for a Grammy for Solo Performance and for Best Jazz Instrumental of 1999. Broad Strokes, issued in 2000, pays tribute to many fellow musicians and features an electronic wash supplied by Sonic Youth. That same year Rudd received a Guggenheim Fellowship in composition. In 2002 he recorded Roswell Rudd and Archie Schepp: Live in New York and Seize the Time with the Nexus Orchestra; and in 2002-03 he served a Jazz Artist Residency at Harvard. The Jazz Journalists Association named him Trombonist of the Year in 2003, 2004, and 2005.

As a composer, Rudd combined the collective improvisatory elements of jazz and ethnic music with the European classical tradition. After years spent working with the Lomax material, Verna Gillis's World Music scene was an easy fit:

What used to be called "comparative musicology" is called "World Music" now. The ivory tower is connected to the street now. This is to a great degree due to Alan Lomax, who went to the Delta, the prairies, the prisons, the bayous - out-of-the-way places where something substantial was going on in American folk music. I am so proud to have worked with him. He recorded bluesmen, railroad workers, chain gangs, cowboys. At the time, that was not even considered music, it was considered anthropology. How wonderful it is to find music where there isn't supposed to be any music! (Quoted in Mike Zwerin, "Jazz Original Returns After 20 Years: Roswell Rudd Is Back," International Herald Tribune, 14 July 1999)

In Mali, Africa, in 2000, Rudd jammed with Toumani Diabate, a griot master of the 21-string Malian kora. "It went so well," Rudd recalled, "that [Verna and I] returned the following year and recorded Malicool," a cross-cultural collaboration with Toumani and other Malian musicians. It was nominated for a Grammy. Reviewer David Dupont wrote, "Unlike other jazz musicians who have used African elements to provide a lot of exotic color, Rudd immerses himself in the African context, with an electric bass and guitar as the only other Western instruments. In Sayan Sisoko's hands the guitar even returns to its Moorish roots" (One Final Note). Rudd and Gillis's 2001 trip is documented in the film, Bamako is a Miracle (now on YouTube). The 2008 Malicool ensemble includes performers from Senagal and Rio de Janeiro.

In 2003, the Mongolian Buryat master throat singer Odsuren and his student, Battuvshin (Tuvsho) Baldantseren, visited Rudd and Gillis in upstate New York. They started to sing and Rudd joined in with his trombone. Rudd believes that both trombone and throat singing share a similar range and sound, that is, strong bass notes with high harmonics (overtones), and highly embellished melodies. Tuvsho returned in 2005 and the Mongolian Buryat Band (so named by Gillis), comprising Rudd, Tuvsho, singer Badma Khanda, and three instrumentalists, recorded Blue Mongol, an album of traditional Mongolian tunes, American gospel hymns, a Malian song, and five original Rudd compositions. In 2006, they toured the United States on the East and West Coasts, and Chicago, and the following year, on a grant from the Trust for Mutual Understanding, Mongolia and Siberia.

Rudd's wife died in 2004. That year, Rudd and Gillis traveled to the Fourth Festival au Desert (in the Sahara) in Essakane, Tombouctou Region, Mali, with Rudd's Trombone Shout Band (now called Trombone Tribe). The band's name and repertoire were partly inspired by the music of the United House of Prayer, an African-American denomination centered on the Eastern seaboard of the United States. It comprised Rudd, Steve Swell, and Deborah Weisz on trombones, Bob Stewart on tuba, Henry Grimes on double bass and violin, and Barry Altschul on drums. The album El Espiritu Jibaro, released in 2006, had its genesis as early as 2002 when Rudd first heard and recorded with one of Gillis's earliest collaborators, Puerto Rican Yomo Toro, the great exponent of the cuatro. The album, featuring drummer Bobby Sanabria and his twenty-six-piece Ascension band, includes cumbia, tango, and merengue dances. Rudd's 2007 recording Keep Your Heart Right introduced a Korean scat singer Sunny Kim (a student of the late Steve Lacy). Rudd, Kim, pianist Lafayette Harris, and bassist Brad Jones formed a quartet, which, in 2007, traveled to Italy. That year Rudd also performed with the Beijing Opera star, Li Xiaofenf.

Rudd also performs with David Oquendo, the Cuban singer and instrumentalist in concerts ranging from pop and jazz standards, Afro-Cuban music, and original works written for the occasion. Of particular interest to Rudd is Oquendo's scat: "He told me that there was a time when drums weren't allowed on the street (in Cuba); you had to have permission to play the drums, so the mouth and body percussion became something of a substitute for playing percussion on the street. . . . There is a lot of street in David."

Rudd and Verna divide their time between New York City and the Catskills. He loves to cook, which suits Verna just fine.

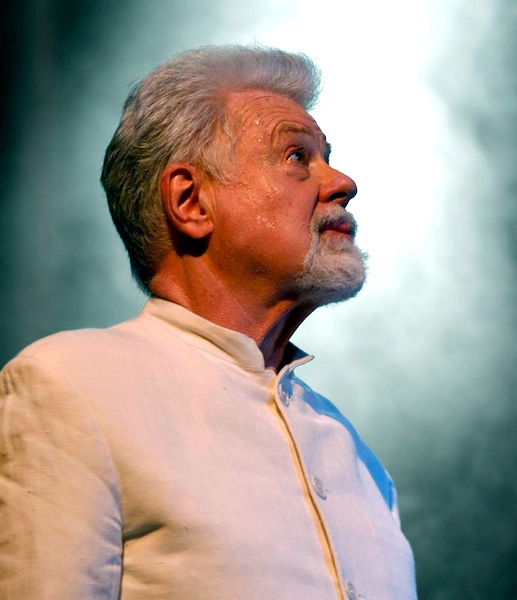

Photo: Roswell Rudd, 2006. Photo by Christian Sahm.