Prepared and written by Ellen Harold, 2008.

Zora Neale Hurston: Three letters to Alan Lomax

The first letter, dated June 7, 1936, was written from Jamaica to Alan Lomax inviting him to join her in folksong collecting in Jamaica and Haiti. About a week later Alan and NYU English professor Mary Elizabeth Barnicle joined Zora in Eatonville, Florida and began a three-week trip beginning in Florida through the Georgia Sea Islands. Alan had convinced the Library of Congress to sponsor Zora, arguing, correctly, that she would be an invaluable guide. He later attributed the success of their trip entirely to her contribution.

In Florida, Zora would famously convince Alan and Barnicle to blacken their faces and hands to avert potential trouble with white policemen enforcing the Jim Crow laws. In spite of this a policeman did arrest Alan, but Zora was able to talk him into releasing him. During the trip, Zora took a dislike to Barnicle and they parted company after Zora objected to Barnicle’s photographing a young man eating watermelon. Alan and Barnicle, therefore, went on to record alone in the Bahamas.

Zora disapproved of Barnicle’s left-wing politics, her drinking, and her collecting methods. In August Zora wrote to the senior Lomax a reassuring letter about Alan, then 20: “I deserve no thanks if I have been helpful to Alan in any way. He is such a lovely person that anybody would want to do all that they could to please him. He will go a long way” (see Zora Neale Hurston to John A. Lomax in Carla Kaplan’s Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters, p. 357). In September she wrote again: “Miss Barnicle is not the disinterested friend of yours that you think. If she has her wish, Allan [sic] will not be back with you for years to come, if ever. She is trying to get him something to do so that he will not return to college this year but will stay here in New York. For one thing, she has a certain attachment to the boy, and the next, she is trying to build herself a reputation as a folklorist thru the name of Lomax. When she proposed that I go on this trip with them . . . [she] urged upon me . . . that I must help her to get this lovely young man out of his stifling [Southern] atmosphere. He had a backward father . . . Leadbelly got no ideas of persecution from the Negroes in the village [of Wilton, Connecticut] as you supposed. He got them right there in the house in Wilton [i.e., from Miss Barnicle]. Why? She was attracted to him as a man by her own admission. And next, she, like all other Communists are making a play of being a friend to the Negro at present and stopping at absolutely nothing to accomplish their ends. . . Allan is being told that he must build himself up independently of you. Ostensibly a build-up for him. But all these activities will center around the English dept at N.Y.U." (Kaplan, 2002, p. 359–60). As it happened Alan did return to Texas to complete his degree and John A. Lomax’s relationship with Lead Belly was at that point irrevocably broken. It does seem, however, that some of the stories about John Lomax’s alleged mistreatment of Lead Belly originated with Barnicle and her circle.

A set of 24 discs that were recorded by Zora Neale Hurston, Mary Elizabeth Barnicle and Alan Lomax in June of 1935 are listed in Series A, Georgia And Florida Recordings, Discs BC:1-24, 1935, Box 7 of the Mary Elizabeth Barnicle - Tillman Cadle Collection at East Tennessee State University.

The second letter, dated late in 1936 was written from Haiti, where Zora had been gathering material for her book, Tell My Horse. In it she advises Alan whom to see in Haiti and what to read for his upcoming trip. Her assurance that: “There is no danger of tropical diseases here,” proved ironic, as Alan and his new wife Elizabeth Harold were to spend much of their three month stay in Haiti in semi-prostration from fevers.

The third letter was, written in 1957, when Zora, in poor health and much reduced circumstances, was valiantly trying to complete a historical novel set in Biblical times. Despite years of obscurity, she still had a healthy sense of her own worth — one that would be amply justified after her death. Her comments on the guitar, coming just as the rock singer with guitar (in the person of Elvis Presley and his imitators) was beginning to take the ascendancy in pop music away from the night-club torch singer and orchestra, are prescient. She was correct in asserting that folklorists like herself and Alan had anticipated and contributed to this grass-roots shift in public taste.

Two transcribed letters (August & Sept 1935) from Zora Neale Hurston to John A. Lomax.

Zora Neale Hurston, August 30, to John A. Lomax

Apt. 2-J

New York City

My dear Mr. Lomax,

Your very kind letter has just reached me here. I see that I should have had it two weeks ago, so it was somehow not forwarded promptly.

I deserve no thanks if I have been helpful to Allan [sic] in any way. He is such a lovely person that anybody would want to do all that they could to please him. He will go a long way.

Because he told me that he plans to take his degree at U. of T. this year and then continue in folk-lore, I carefully insisted that he see further than the surface of things. There has been too much loose talk and conclusions arrived at without sufficient proof. So I tried to make him do and see clearly so that no one can come after him and refute him.

He has such great admiration for you that I’m certain that your love for him is not greater than his for you. He says that he is just seeing you as you are and appreciating your bigness and your tenderness.

Don’t be cross with him, but he told me how you used to take him in your arms when was a small boy & restless and walk the sidewalks with him and sing to him and tell him tales. I saw him myself turn his back on all urgings [from Elizabeth Barnicle] to come to New York this fall. “My father has plans for me and he is right, too. I am just seeing that he knows best.”

On another occasion he repudiated the Communist Party for the same reason. “It is just as my father says. I couldn’t, wouldn’t hurt him ever again by refusing to accept his judgment in such matters.” He kept me up until four o’clock in the morning one night talking about John Lomax. So I have a tremendous, shall I say curiosity? about you as a man, and a huge interest in you as a folk-lorist.

Thanks for any notice you might take of me in the work. I regret that the time was so short. Hope to mend the lick next time if there ever is a next time. I have resolved to bring Allan [sic] to the notice of Dr. Boas. He told me that Boas was very cold to him when he went to see him. But I shall introduce him in a way to catch the eye of Boas.

Thanks again for your kindness. If ever you are in New York City please look me up. I should like to discuss certain phase of the work with you.

Sincerely,

Zora Neale Hurston

August 30, 1935

Zora Neale Hurston September 16, to John A. Lomax

1925 Seventh Avenue

New York City

Sept. 16, 1935

My dear Mr. Lomax,

I thought once that this letter would not be necessary, but what I heard two nights ago makes me feel that it is.

Miss Barnicle is not the generous disinterested friend of yours that you think. If she has her wish, Allan [sic] will not come back with you for years to come, if ever. She is trying to get him something to do so that he will not return to college this year, but will stay here in New York. For one thing she has a certain attachment to the boy and the next, she is trying to build herself a reputation as a folklorist thru the name of Lomax.

When she proposed that I go on this trip with them, one of the things she earnestly urged upon me was that I must get this lovely young man [in --] out of his stifling atmosphere. He had a backward father who was smothering Allan with fogy ideas of both mind and body. I heard how you took that gentle poet and artist Leadbelly and dogged him around, and only her sympathetic attitude and talks with him (when you were not present, of course) kept the poor fellow alive and believing in himself. Leadbelly got no ideas of persecution from the Negroes in the village as you supposed. He got them right there in the house in Wilton. Why? She was attracted to him as a man by her own admission. And next, she, like all other Communists, are making a play of being the friend of the Negro at present and will stop at absolutely nothing, absolutely nothing to accomplish their ends. They feel that the Party needs numbers and the Negro seems to them the best at present. They just don’t know us is the reason they feel that way. One of the things that she is working hardest for is that Allan shall not return to Texas this fall. She says he does not need the schoolin and he needs New York and freedom. I promised that I would help all I could to persuade him to that end. But, Mr. Lomax, when I met Allan and he told me his plans and talked about you in the way he did, I just could not find it in my heart to help destroy the boy. That is just what it will amount to in the end. I know whereof I speak and I would much rather confront her in front of you than write this letter. She even gloated that she meant to take your daughter [Bess Lomax], whom she describes as a beautiful intelligent creature who is also being ruing by your cruel control, and let her “grow.” Your name came up in a restaurant Friday night were I sat at a table. Two men present were Reds, and they spoke of how at Miss Barnicle’s house they heard of your holding poor Allan down/

When I left Allan in early August he was in the notion of doing what you wished. Saturday night he came here and told me that he did not intend to return to Texas unless he couldn’t find anything to do here. That you had written urging him to come home as soon as possible, but that he wasn’t going to if he could help it. So you see, what she said was her objective on this trip South seems accomplished. I have not mentioned details and incidents because that would be too tiresome but I do know what I am talking about. And none of this would add to your happiness. She knows that I see through her and do not approve. She has used a great deal of sophistry on Allan to cover up and I have merely let him know that I do not think that she is clean. He is so terribly young and men are so dumb for the most part before the tricks of women anyway. He merely sees himself hugely approved of and urged to free himself of all inhibitions. The very things he had been told at home were indecent and to be avoided like the plague.

You know very well that I would not take the liberty of saying these things if I had not plenty of proof to back it. Out in the Bahamas MANY folks felt that both the white race and Americans had been shamed. Further, the works of John and Allan Lomax are being deviously diverted to the works of Elizabeth Barnicle. Allan is being told that he must build himself up independently of you. Ostensibly a build up for him. But all these activities will center around the English dept. at NYU.

Don’t take my word for it. Investigate. Wish that you could happen up here unexpectedly.

Allan has promise. I was outraged that she opposed every effort on my part to make him a serious worker. Selling him the idea that the way to collect folk-lore was to stay half drunk. Horrible to me from the view point of a worker who feels that one needs all one’s faculties plus every mechanical help to do the job. And then again from my small-town Florida background to see a fifty-year-old woman plying a twenty-year-old kid with likker.

I am not asking you not to say I told you for I am so sure of my facts that I don’t care. But it would be nice if you just watched developments on your own. She knows that I know, oh God, just too much, but I am certain that she feels sure of you to the extent that you would never believe a word against her. Further that you are a white Southerner and I am a Negro and so I am certain that she feels that she could be daring and you would never believe me. For that reason I wish that you could wait awhile and see what happens and interpret events in the light of what I have told you.

Most sincerely,

Zora Neale Hurston

What I meant to say is that at present she is making him feel that he has arrived at the place where he can stand alone and is a folk-lorist independent of your reputation and consequently does not need you nor any further education. You know that both those conclusions are very pathetic and will be disastrous for him.

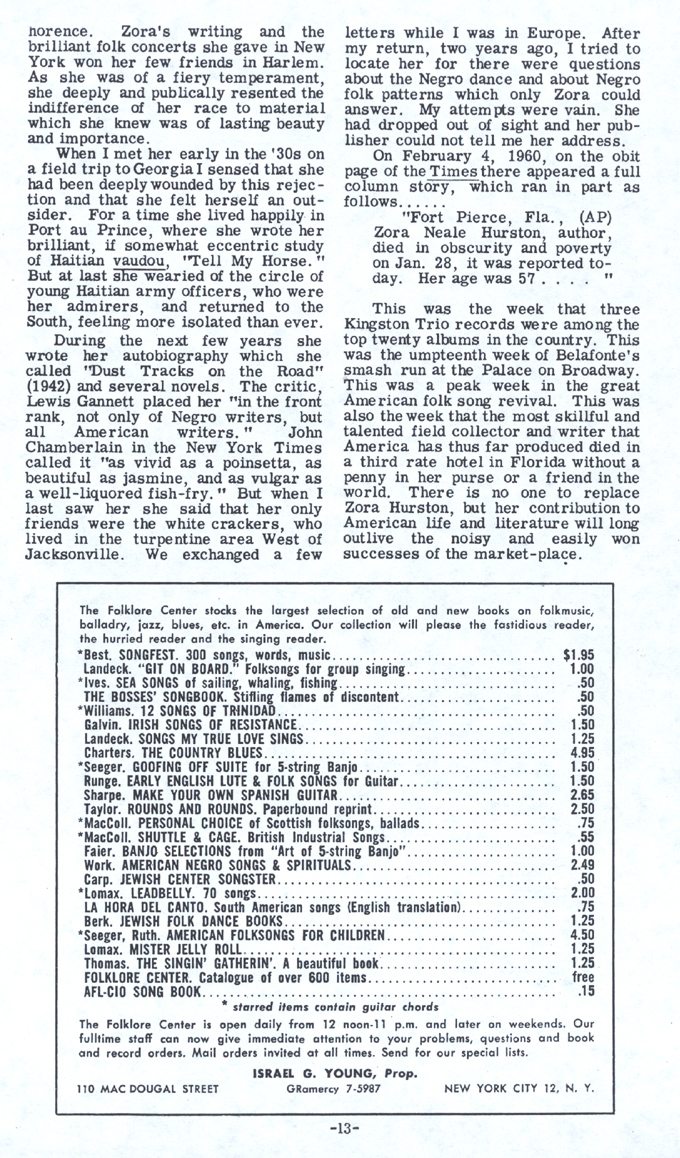

The following article appeared in the July 1960 issue of Sing Out! on the occasion of Zora’s death as a virtually forgotten figure.

Some notes on Zora Neale Hurston and the Lomaxes. Zora Neale Hurston's 1938 work for the WPA

When Zora Neale Hurston joined the WPA's Florida Writers' Project in 1938, Project head, Henry Alsberg, who was a liberal, wrote from Washington, D.C., to Corita Dogget Corse, director of the Jacksonville office, urging that Zora be hired as an editor. As an editor, however, she would have been supervising whites, and local racial attitudes precluded that. Instead, Corse set aside some extra money for Zora's travel expenses. John A. Lomax, who had served as folklore consultant to the WPA from 1936-37 had by this time been replaced by Benjamin Botkin, but Zora's previous experience recording for the Library of Congress with Alan Lomax and Mary Elizabeth Barnicle in 1935 enabled her to borrow a Library of Congress recording machine to collect folk music with Stetson Kennedy in conjunction with the WPA project.

"Jim Crow," Kennedy wrote, "was looking over our shoulders":

It being unthinkable in those days for white and black (much less if they were also male/female) to travel together, Dr. Corse hit upon the scheme of sending Zora ahead as an advance scout to seek and find people with folksong repertoires; I would follow with the machine and staff photographer Robert Cook. There being virtually no overnight accommodations for blacks, Zora frequently had to sleep in her Chevy ... In looking back, we WPA treasure hunters felt a bit conscience-stricken about hard-up informants who hoped to be paid a little something for singing their hearts out for posterity. Uncle Sam had not included so much as a dime for such purposes in the treasure hunt budget. But since we were just as hard-up as our informants, there was nothing we could do but say "Thank you." Perhaps posterity, as it visits their Website, will add its thanks to ours. - Florida Folklife

More on the story of their experiences can be found here.