by Peter Stone

Adel Hall (aka Vera Hall, Vera Ward, Vera Ward Hall, and Adel Ward) was born in 1902 in Paynesville, just outside of Livingston, in rural Sumter County, Alabama. During her lifetime few outside her local community knew of her talents, but many now recognize her from Moby's 1999 album, Play, whose hit track, "Natural Blues," sampled Hall's 1937 recording, "Trouble So Hard" (From Alan Lomax's 1959 Sounds of the South, LP series). The Library of Congress used Vera's "Another Man Done Gone," recorded on October 31, 1940, in its commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation (on A Treasury of Library of Congress Field Recordings, Rounder CD 1500, 1997). In 1943 the BBC aired her version of "Another Man" as an example of the best of American folk music. Alan Lomax's book, The Rainbow Sign: A Southern Documentary(New York, Duell Sloan and Pearce, 1959), was based partly on taped interviews with Hall (whom he called "Nora" to protect her privacy).

Vera Hall began singing religious songs learned from her mother, Agnes, a former slave, and her father, Efron "Zully" Hall, and at the local Baptist church. A friend, Rich Amerson (a harmonica player and singer who sings "Hog Hunt," among other songs on the Deep River of Song: Alabama CD) taught her the Piedmont style of blues. As a child, she often baby-sat, and she worked most of her life as a cook, washerwoman, and nursemaid, but she always sang, her beautiful voice gaining some national attention only in the late 1930s.

Vera and her cousin, Dock Reed, with whom she often sang religious duets, were raised among strict Baptists who forbid "worldly songs" — the "devil's music," as they called it. Dock honored those restrictions, but Vera did not. In despair over the death of her mother, she had withdrawn briefly from her church and turned to the whiskey-soaked milieu of the blues. She found that singing them eased her troubles and continued to do so, even after rejoining the congregation: "I don't sing um around nobody. I go off in the kitchen and close the door before I sing a blues that fits my case." She even described how once, when the church officers once "handled" (reprimanded) her for singing blues for white folk collectors, she successfully defended herself: "I told those old deacons the truth, "I did sing the blues. I give um the words and showed them how the tune went — just trying to do what I was asked to do; but that didn't have no effect on my religion"(The Rainbow Sign, page 103).

In 1937, Livingston resident Ruby Pickens Tartt (1880–1974), first brought Vera and Dock to the attention of John A. and Ruby Terrill Lomax on their trip through Alabama to record African-American folk lullabies, play songs, and blues for the Archive of American Folk Music of the Library of Congress. Mrs. Tartt, a writer, painter, and amateur folklorist had supplied New York writer Carl Carmer with material for his 1934 bestseller, Stars Fell on Alabama. She became chairperson of the Writer's Project of Sumter County " an agency of the WPA for which John A. Lomax was a consultant. (From 1940 to 1964 she served as Sumter County Librarian and the Public Library of Livingston now bears her name.)

John A. and Ruby recorded Vera and Dock, among others, at various times from 1937 to 1940. It was on the Lomax's 6,500-mile-1939 journey through the American South that they captured, in a six-day stop in Livingston, the performance on May 26 of "Amazing Grace" by Vera, Dock, and Jesse Allison for the Archive (AFS 2684 A1). (The results of that trip are available on the Library of Congress recording, Southern Mosaic: The John and Ruby Lomax 1939 Southern States Recording Trip.) The trio sings an ornamented version of the now standard "New Britain" tune with the lined-out "Amazing Grace" lyrics (as they were first joined in The Southern Harmony of 1835).

The breadth of Vera's repertory and her masterful artistry with blues and traditional songs are comparable to those of Lead Belly and Jelly Roll Morton. The Lomaxes note: "If Vera can hear a song through once or twice, she can sing it again herself, with perhaps a variation or two of her own, always an improvement."

The Rainbow Sign resulted from notes taken by Alan Lomax and Elizabeth Lyttlton Lyttlton [[Lyttleton]] Harold during a 1948 visit by Vera and Dock to New York, where Alan had brought them for an American Music Festival concert at Columbia University (held on May 15, 1948.) He wrote of her:

Her singing is like a deep-voiced shepherd's flute, mellow and pure in tone...The sound comes from deep within her... from a source of gold and light...It is a liquid, full contralto, rich in low overtones; but it can leap directly into falsetto and play there as effortlessly as a bird in the wind.

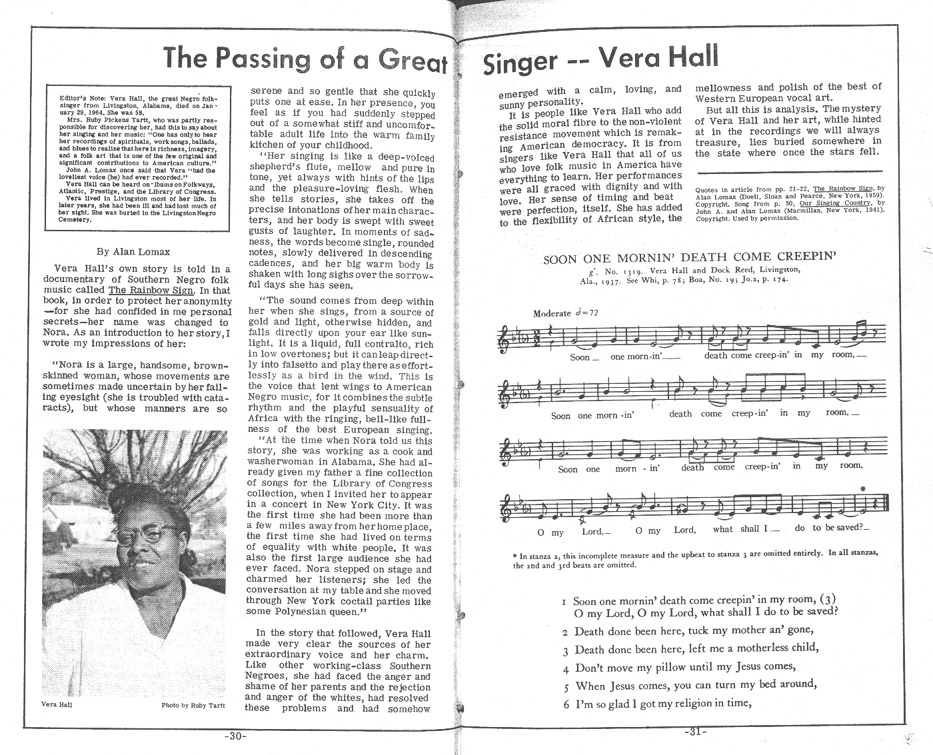

At the time Alan and Elizabeth interviewed her, Vera's sight was already dim from cataracts. She died, blind and destitute at Tuscaloosa's Druid City Hospital on January 29, 1964 and was buried in Morning Star Cemetery in Livingston, like many African Americans in this part of the country, in an unmarked grave. Her first child, Minnie Ada, born in 1917, had predeceased her, as had her husband, Nash Riddle (a coal miner killed in 1920), her sister, and two grandchildren.

On March 3, 2005, Vera Hall was inducted into the Alabama Women's Hall of Fame at Judson College in Marion, Alabama. She was further honored with the dedication, on April 21, 2007, of a plaque celebrating her musical legacy placed in Livingston by the Livingston Historical Commission and the Alabama Blues Project of the University of Western Alabama. The historic marker was made possible by donations from, among others, the musician Moby, and Anna Lomax. Vera Hall can be heard on Atlantic's Sounds of the South LP recordings and CD reissues; and also on the following Rounder CDs: Afro-American Spirituals, Work Songs, and Ballads (Rounder 1510); Southern Journey, vol. 1, Voices from the American South; Southern Journey (1701), vol. 6, Sheep, Sheep, Don'tcha Know the Road? (Rounder 1706); and Deep River of Song: Alabama (Rounder 11661-1829-2).